THE UNRAVELLING OF SCIENCE

“Facts no longer made contact with the theory, which had risen above the facts on clouds of nonsense, rather like in a theological system. The point was not to believe the theory but to repeat it ritualistically and in such a way that belief and truth became irrelevant.” English Philosopher Roger Scruton, 1980

The development of the Scientific Method was one of the great achievements of the Enlightenment of the 17th and 18th Centuries. The method is based on three pillars: reproducible evidence, deductive reasoning, and hypotheses that can be tested by experiment. It freed scientists from the introspection, preconception, prejudice and reliance on authority which, for centuries, had held back knowledge and understanding of the physical world. The Scientific Method is the only means yet devised that enables a judgement to be made on the extent to which new ideas or hypothesis might approach enduring objective truth (1), or are merely a product – as relativist Post-Modern Philosophers would maintain – of the ephemeral mores and fashions of the society in which the scientist lives. Over the last 300 years, the Scientific Method has proved astonishingly successful, improving almost every aspect of our lives. This has given science and scientists a near universal authority and respect.

But a profound change took place in the way that many scientific disciplines came to operate from the nineteen fifties onwards. The most instructive early example of this trend came from the field of Epidemiology. In North America, many in society were concerned about the deadly impact for human health and life of a perceived epidemic of heart disease. In 1955, President Eisenhower’s heart attack brought this problem great publicity. But traditional (or normal) science, based on the long-established scientific method, was able to offer no definite answers to this problem, or advice to policy makers. Their honest response would have been… “we don’t know the answer to this problem, if indeed there is a problem, or even an answer; it could be this, it could be that; but we’re working on it”.

Faced with the dilemma of only being able to offer equivocal soft solutions for a perceived hard societal problem, some scientists resorted to statistical correlations as a substitute for actual evidence. This inevitably resulted in the collection of gigabytes of data that were open to multiple interpretations. In this swamp of fuzzy data, they navigated on the basis of personal belief and perceived social need. Opinion-based evidence came to be offered in place of evidence-based opinion. Their conclusion, which at the time gained an almost universal acceptance, was that the epidemic of heart disease resulted from our over consumption of fat (2). The idea that dietary fat caused heart disease was then offered to Governments as policy advice. It was claimed as Settled Science, but the conclusion had not been arrived at through the normal scientific method but as a result of expert judgement (opinion), reinforced by a consensus of peers (fellow swimmers in the swamp). With their core beliefs involved, the consensus scientists had little tolerance of the doubts of those who did not share these beliefs. Those who disagreed were not just mistaken, but seen as morally corrupt as well.

It would take 50 years, and immense damage to public health, before these conclusions and policy prescriptions were exposed as false, although the lingering effects of the fat phobia are still with us today. But for that 50 years, the technique had been astonishingly successful for the scientists involved, giving them fame, influence and status.

In the meantime, and not surprisingly, the same mode of doing science was being employed to allow scientists in other disciplines to tackle other perceived existential threats to humanity, most notably in perceptions of imminent environmental and ecological collapse. From the 1980s onwards, many of these environmental fears coalesced around the narrative of Catastrophic Anthropogenic Global Warming or CAGW. The main methodological difference between the way the earlier fat scare and the CAGW scare were approached is that, with the advance of technology, global warming proponents were able to offer computer simulations as a substitute for evidence and a vehicle for expressing their opinions.

It is too soon to tell the story of the Global Warming meme. We are still in the middle of that story, and – unlike the Great Fat Phobia of the last Century – do not yet know its ending.

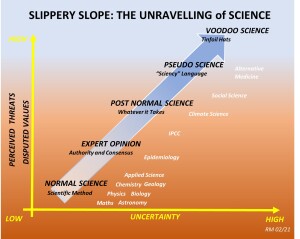

When someone says “..trust the science” or, “.. follow the science”, which type of science are they thinking of ? And how would they even know ? For answers to these questions, see text.

All these features add up to what has been called, by the philosophers of science Silvio Funtowicz and Jerome Ravetz (3), as Post-Normal Science. Normal scientists see themselves as seekers of truth and knowledge. Post-normal scientists see themselves as White Knights riding to save humanity and speakers of Truth to Power. Driven by passion and emotion, they avoid the checks and balances of traditional scientific communication by promoting themselves and their research to a wider audience through press release, op-ed, blog and tweet.

“The urge to save humanity is almost always the urge to rule” - H.L. Menken

The methods of Post-normal scientists are the antithesis of the classical Scientific Method: their evidence is often not reproducible, their hypotheses not falsifiable and their reasoning directed towards achieving a predefined goal determined by social mores. It is a process which claims, and by many has been granted, the authority of normal science for what is, in effect, social activism.

This is not to dispute the expertise of these scientists. They have skills and knowledge that are widely acknowledged and accepted by society and therefore deserving by them of respect and consideration. But by these criteria, the same “expert” label could have been applied to the Stone Age Shamans who knew how to placate the Gods, the Haruspices of ancient Rome foretelling the future from the entrails of chickens, the Witch Finders of the 16th Century, the Astrologers of the 17th, the bloodletting Physicians of the 18th, the scientific racists of the 19th or the Eugenicists of the 20th (reaching their logical conclusion with the holocaust).

It is easy to laugh (or shudder) and feel smug at the irrationality of our ancestors’ beliefs, but how will our descendants view ours? One hundred or two hundred years from now, we can be more than confident that e will still equal mc squared, that hydrogen will still have atomic number 1 and that the earth will still be around 4.5 billion years old. That level of confidence comes because these are examples of knowledge derived from Normal Science. But there is no guarantee that the expert judgments and consensus positions of Post-normal Science will fare so well.

“the aim of life is not to align oneself with the majority but to avoid finding oneself in the ranks of the insane” – Marcus Aurelius, 2nd Century AD

Not all sciences are affected by this corruption. Physics, Chemistry, Astronomy, Mathematics, Geology (and many others) remain, for the most part, pure, but there is a grain of truth in the saying: never trust a Science with an adjective in front of it. Climate Science, Dietary Science, Environmental Science, Social Science, Political Science… all attempt to steal the respect and credit, hard-won over centuries, of the physical sciences. Lord Kelvin (William Thomson) put this idea at its most brutal in his typical didactic Scottish way, “all science is physics, all the rest is stamp collecting”. Nowadays, we just call it physics envy, but the motivation for naming a field of study “science” is all too often not envy, but an attempt to harness respect and authority for personal, political or monetary ends.

There is a gradation that ranges from the relative certainties of Normal Science, through Expert Opinion, Post-normal Science and Pseudo-science to the deranged theories of what can only be described as Voodoo Science. At all points on this gradation are systems of methodology and belief claiming the title and authority of Science. What degree of acceptance, scepticism or outright dismissal should be given to their theories and prescriptions? Is there a guide?

Yes, there is. The late, great, Carl Sagan offered such a guide. In his 1997 book (Random House, 457 p): The Demon-haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Wind, Sagan presented nine criteria for recognising good science. He called it his Science Baloney Detection Kit (4), (5). The “kit” is a check list for the Scientific Method. Here is the list:

- There must be independent confirmation of the “facts”.

- Debate on the evidence by knowledgeable proponents of all points of view must be encouraged.

- Arguments from authority carry little weight.

- More than one hypothesis must be offered and considered.

- Proponents must not become too attached to a hypothesis just because it is theirs.

- Quantifiable evidence carries more weight. Vague and qualitative is open to too many explanations.

- If there is a chain of argument, every link in the chain must work, including the premise.

- Apply Occam’s Razor.

- Every hypothesis must be, at least in principle, capable of being falsified.

To which the present author would add a tenth:

10. All areas of uncertainty must be openly acknowledged.

Many claim the respect and authority for their ideas and beliefs that comes with the mantle of science. The ten criteria above provide a means for anyone to judge the amount of respect and authority that their ideas merit, and where to place their beliefs and ideas on the slippery slope of science.

*******

(1) For a discussion of the meaning of the words fact and truth and how they are used and misused in debate , see my post: The purpose of science is to seek truth, not proclaim it « Roger Marjoribanks Roger Marjoribanks

(2) For a detailed description of the birth, life and death of the great fat phobia of the latter half of the 20th Century, see my earlier post: Fear of Fat

(3) Silvio Funtowicz and Jerome Ravetz 1990: Uncertainty and Quality in Science for Policy. Kluwer Academic Publishers 231 p, ISBN 978-94-009-0621-1

(4) https://www.brainpickings.org/2014/01/03/baloney-detection-kit-carl-sagan/

It is also worth noting Sagan’s final disclaimer: “Like all tools, the baloney detection kit can be misused, applied out of context or even employed as a rote alternative to thinking. But applied judiciously, it can make all the difference in the world – not least in evaluating our own arguments before we present them to others.”

(5) Michael Schermer, Founder of The American Sceptics Society and Editor-in-chief of its magazine Sceptic, is a self-appointed arbiter of all things sceptic. Schermer borrowed Carl Sagan’s idea and title and produced his own Science Baloney Detection Kit ( Search | Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science ). However, lacking Sagan’s wisdom and grounding in physical science (Sagan was an Astronomer and Historian of Science: Schermer a Psychologist and Social Activist), Schermer threw out most of the items from Sagan’s list that relate to the Scientific Method and substituted instead a vague and subjective set of criteria, some of which I reproduce below. These criteria encourage and permit anyone to be sceptical towards ideas that do not match their established beliefs, thus facilitating a warm glow of moral superiority at no cost to their World View.

Here are some of the items from Schermer’s bowdlerized version of Sagan’s Baloney Detection Kit (my comment appended in italics):

- Does this fit with the way the world works? (i.e. judge on the basis of your existing beliefs).

- Does the claimant provide proper evidence? (“proper evidence”; definition: the evidence that you expect or want to hear).

- How reliable is the source of the claim? (“reliable source”; definition: one supported by authority and consensus).

- Have the claims been verified by someone else? (depending on the meaning of “verified” – which Schermer does not provide – this will be read as a restatement of the consensus fallacy – argumentum ad consensum: the more people that believe something, the more likely it is to be true).

The scepticism of Michael Schermer and Richard Dawkins is largely directed towards debunking the soft targets offered by Pseudo-Science and Voodoo Science, but they seem blind to today’s creeping rot of expert judgement, argument from authority, consensus and Post-Normal Science. To be fair to Schermer and Dawkins (both heroes of mine from other contexts), they are engaged in a battle with the crazies, and are probably reluctant to give away ammunition by publicly aiming their scepticism at the more established sciences that lie further down the slippery slope.