The Mathew Effect and other Problems of Science

Dr Norman [1], a young scientist at the start of her academic career, writes a technical paper full of new observation and innovative ideas challenging accepted orthodoxy and submits this to a prestigious international Journal. Norman is happy to acknowledge minor, but valuable, input from her friend and colleague Dr Edwards and includes him as a co-author. Professor Yelland, the head of her department, must also be included as a co-author because it is his policy that all papers from his fiefdom carry his name. This is a very common practice, which the Professor justifies by saying that he is the Head of a Team and, by virtue of his reputation and contacts, all members of the team are beholden to him for their contracts, salaries, funding and (he likes to think), intellectual leadership.

But the Professor has another policy: authors of joint papers must list their names alphabetically. Were Norman’s paper to be submitted in the order of their relative contributions, as Norman, Edwards & Yelland - it would, correctly, establish Norman as the lead author. But under Yelland’s direction, she is forced to publish it as authored by Edwards, Norman and Yelland. An important distinction, as we shall see.

Why this policy? The Professor justifies it by saying:

“We are all equal members of a democratic team – there are no prima donnas here. The more authors a paper has, the more authority it can claim”.

But there is an unspoken reason: one that everyone involved understands:

No one can be allowed to outshine their boss. With an alphabetically arranged author list, most will assume that my name comes last only because of my position in the alphabet.

You think that’s petty? And so it is, but anyone who has worked in the dog-eat-dog world of academia will recognise that such selfish stratagems are par for the course (2)

For Edwards, with the paper published, widely cited as Edwards et al. and winning prizes, there is Tenure and, on the future retirement of Yelland, appointment as the new Head of Department. To Professor Yelland’s already large bibliography is added another starred item: his reputation boosted: fresh research grants and new acolytes assured. Norman’s academic career languishes. Unable or unwilling to renew her contract, she resigns and seeks a position in industry where the harsh realities of commerce ensure that talent is rewarded on the basis of results, not reputation

But Norman, Edwards and Yelland can consider themselves lucky. If their study had been in the highly-politicised field of Climate Science, it is likely their paper would have been rejected. Today, most Journal editors are employees of science publishing companies. If an editor – seeking a contest of ideas and open debate – were to accept a paper that challenged Climate Change orthodoxy, then said editor would run the risk of being fired. Why? Bear with me with me while I follow the money. Science publishing companies make money from consumers of their products through a subscription-based model. The money involved is huge: the publishing company Elsevier (with more than 3000 science Journals on their books) made a profit of $4.2 billion in 2024 (Internet search). The consumers are the world’s universities who pay on the number of clicks made by the registered users of their libraries: the more clicks, the higher the fee. Universities today get their funding largely from governments who wish to promote research consistent with their ideological and political ends. In the Western World, these ideologies typically involve alarmist views on climate change. So we return to where we started: a vicious ouroboros loop: a snake eating its tail. This snake is not a perpetual motion machine. It is fueled and directed by government money.

The ouroboros snake: the original vicious circle.

The ouroboros snake: the original vicious circle.

My story of Dr Norman is a parable that illustrates many things, among them:

- turning your back on truth in favour of empathy, consensus and inclusion.

- self-serving behaviour at the expense of others.

- the “publish or perish” requirement for academics if they want promotion.

- The role of governments in controlling the direction of scientific research, and..,

- success itself, whether deserved or not, can be self-reinforcing.

The last bulleted point is an example of the Mathew Effect [3]. The Effect is named from scripture:

“For unto everyone that hath, shall be given: and he shall have abundance. But from him that hath not, even that which he hath, shall be taken away.” St. Mathew Gospel, 25:29. (King James Bible translation).

The term Mathew Effect was first coined in a 1968 [4] paper in the journal Science by Robert K. Merton – a professor of sociology at Columbia University. In Merton’s abstract, the Effect is defined as:

“…a conception of ways in which certain psycho-social processes affect the allocation of resources to Scientists for their contributions – an allocation which in turn affects the flow of ideas and findings [5] through the communication networks of Science.”

(Saint Mathew and his English translators put the idea much more succinctly).

The Mathew Effect is a cynical and bleak observation on how success can breed success: how reputation and authority can become self-sustaining: how rigid orthodoxy can exclude new ideas, potentially giving one person or small elite in-group at the head of every discipline an authority they may not deserve. The Mathew Effect can be seen in all fields of human endeavor but is most noticeable in the organised and structured disciplines of universities.

With the aid of hindsight, examples of the Mathew Effect are easy enough to find. I have chosen a just few from the wide field of science:

- In 1543, Nicolaus Copernicus - a scientist and catholic monk- published his theory that the Earth and the planets circle the sun and not, as the scientific and theological paradigms of the time held, the other way round. Those who accepted and promoted Copernicus’ mathematical arguments were fiercely persecuted. In 1600, philosopher Giordano Bruno was tortured then burned at the stake for (among other things) his heretical Copernican beliefs. In 1632, Galileo Galilei was put on trial and shown the torture implements of the Inquisition. He sensibly made a public recantation. That saved his life, but he was put under lifetime house arrest, and his books on astronomy were banned. Science eventually moved on under the overwhelming weight of evidence that the earth is not the immobile center of the Universe, but the Catholic Church’s ban on the works of Copernicus and Galileo remained for the next 200 years (6).

- In 1883, English polymath Francis Galton, influenced by Charles Darwin’s Theory of Natural Selection, proposed selective breeding as a means of improving the human race. He called his proposed new science Eugenics. By “improving”, Galton and his followers meant creating more people like themselves. As rich, white, educated, Northern European males they proposed, amongst other measures, coercive sterilisation of poor, uneducated women. In the United States that usually meant black women. Over the next 60 years in Europe and North America eugenic ideas became widely popular and a field of study for university academics and for implementation by government agencies. Well known figures such as Arthur Balfour, Winston Churchill, George Bernard Shaw, Bertrand Russel, Leonard Darwin (Charles Darwin’s son), John Maynard Keynes, Ronald Fisher (pioneering biostatistician) and Julian Huxley supported the movement through the 1910s, 20s and 30s. To their credit, the Catholic Church under Pope Pius XI (1922-1939), as well as left wing politicians, argued against the movement. In 1931, the UK Conservative Government’s Sterilization Bill for Mental Defectives was rejected by Parliament due largely to opposition from Catholic and Labor MPs. But throughout the Western World, government-supported programs of coercive breeding and forced sterilisation were widely adopted. In Sweden, sterilisation for eugenic reasons began in 1906 and was formalised by Law in 1934. These were supposed to be “voluntary” sterilisations, but it has been shown that in Sweden extreme coercive measures were used, and the victims, numbering in the tens of thousands, were mostly poor, uneducated women. The Swedish Law was only abolished in 2013. In the USA, forced sterilisation for eugenic reasons began in the early 1900s. In 1927, in an 8:1 opinion on Buck v Bell, the US Supreme court ruled that forced sterilisation did not violate the Constitution. Chief Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. affirmed that compulsory sterilisation Laws for the “feeble-minded”, such as had been applied by the State of Virginia to Carrie Buck, prevented the Nation from being “overwhelmed by incompetents” and that “three generations of imbeciles was enough”. Carrie Elizabeth Buck was no imbecile but a powerless poor black woman; for her full horror story go to www.wikipedia.com/carrie-elizabeth-buck). But for all the excesses of Sweden and the United States, the most enthusiastic adopter of Eugenics principles was the National Socialist Government of Germany between 1933 and 1945. The Nazis, in an attempt to produce a pure-blood stock of Aryan Übermenschen, called their eugenics program Racial Cleansing. Übermenschen are a class of superior human beings designed to rule us all. The program took eugenics to its logical conclusion and involved mass murder as well as selective breeding. It was the post-war realisation of the full horrors and scale of Nazi genocidal programs, along with better scientific knowledge on how genetic inheritance actually works, that finally discredited the Eugenics movement.

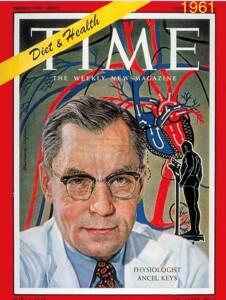

- In in the late 1940s, it was noticed that there was a noticeable rise in the number of people (mostly men) dying from coronary heart disease or CHD. A few sensible scientists pointed out that CHD was strongly age- related and the rise simply a reflection of increased longevity (i.e. good news, we are living longer). But scientists often scorn simple explanations in favour of explanations from the fields of esoteric knowledge that they have spent long years acquiring. Dr Ansel Keys (Professor of Physiology at the U. of Minnesota and the developer of the eponymous K-Rations for US infantrymen in WW2) and cardiologist Dr Paul Dudley White (the Head of the American Heart Association, AHA) called the rise an epidemic and laid the blame solely at overconsumption of fat (meat, dairy, eggs) in our diet. Using United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) data, Keyes in 1953 published (7) a graph showing a compelling linear correlation between dietary fat consumption and deaths from CHD in six countries (USA, Canada, UK, Italy, Australia & Japan). But the paper was a piece of egregious scientific finagling. If Keys had used the full data set of 22 countries available from the FAO, there would have been no neat correlation. Before plotting his graph, Keys simply omitted data from countries that were inconvenient to his story (8). But criticisms of Key’s paper came too late. The Dietary Fat = CHD meme had already escaped, like a virus from a Wuhan Lab, and spread around the world. The idea rapidly became near the unanimous scientific opinion of university departments, learned Academies and Government Agencies. Ansel Keys made the cover of Time Magazine in 1961. The income of the AHA soared from $1.5 million in 1949 to $26 million in 1962, and it continued to rise (9).

Time Magazine: the bellwether for fashionable ideas. In 1976, the US Committee on Nutrition published a survey that showed 98.9% of “nutritionary scientists” supported the dietary fat/CHD connection. The phrases Follow The Science, The Science is Settled, Consensus of Experts and Scientists Say,. were used by activists and repeated endlessly by media and politicians (in a different context, these slogans are still being used today). The few dissenting scientists (presumably from the 1.1% minority of the survey) were sidelined, cancelled or fired. This was the Mathew Effect in operation. But eventually – it took 50 years – heroic clinical trials involving hundreds of thousands of people tracked by surveys over periods of up to 40 years, showed no evidence that dietary fat causes CHD. Major data reviews (meta-analyses) by the Cochrane Collaboration (acknowledged as the gold standard of epidemiological reviews) and others in 2000, 2001, 2004, 2007 and 2012 concluded: “there are no clear effects of dietary fat changes in total cardiovascular events” (10). The scare was over, good science had driven out the bad, but the harm it caused lives on to this day. It has been argued that the present-day surge in obesity and Type-2 Diabetes is the direct result of the “Great Diet Shift” that took place during the latter part of the 20th century, where whole populations in the Western World moved away from meat and dairy to diets high in carbohydrate (bread, pasta, potatoes, rice, sugar). For more information and detail on the great fat scare (lipophobia) of latter half of the 20th century, go to my earlier blog post HERE.

Time Magazine: the bellwether for fashionable ideas. In 1976, the US Committee on Nutrition published a survey that showed 98.9% of “nutritionary scientists” supported the dietary fat/CHD connection. The phrases Follow The Science, The Science is Settled, Consensus of Experts and Scientists Say,. were used by activists and repeated endlessly by media and politicians (in a different context, these slogans are still being used today). The few dissenting scientists (presumably from the 1.1% minority of the survey) were sidelined, cancelled or fired. This was the Mathew Effect in operation. But eventually – it took 50 years – heroic clinical trials involving hundreds of thousands of people tracked by surveys over periods of up to 40 years, showed no evidence that dietary fat causes CHD. Major data reviews (meta-analyses) by the Cochrane Collaboration (acknowledged as the gold standard of epidemiological reviews) and others in 2000, 2001, 2004, 2007 and 2012 concluded: “there are no clear effects of dietary fat changes in total cardiovascular events” (10). The scare was over, good science had driven out the bad, but the harm it caused lives on to this day. It has been argued that the present-day surge in obesity and Type-2 Diabetes is the direct result of the “Great Diet Shift” that took place during the latter part of the 20th century, where whole populations in the Western World moved away from meat and dairy to diets high in carbohydrate (bread, pasta, potatoes, rice, sugar). For more information and detail on the great fat scare (lipophobia) of latter half of the 20th century, go to my earlier blog post HERE. - In the early 1980s, Barry Marshall and Robin Warren were medical researchers at the University of Western Australia. They discovered that gastric (or peptic) ulcers are caused by gut infection with the bacterium helicobacter pylori and not, as the medical establishment had believed for over a century, by stress, spicy food, excess stomach acid, smoking, alcohol, whatever – the only treatment being offered horrendous invasive surgery (which did not actually work). In 1983, Marshall and Warren submitted their findings to the Gastroenterology Society of Australia. It was rejected by their reviewers as among the worst submissions they had received that year. The paper was subsequently published in 1984 by the Lancet (https://doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(84)91816-6 ). The publication was opposed by conventional medicine which held that bacteria could not survive in the acid environment of the stomach. Despairing of a breakthrough, in 1987 Marshall drank a culture of helicobacter pylori that he had obtained from his patients. Within a few days, he was suffering all the unpleasant symptoms of an active gastric ulcer. Marshall then quickly cured himself with a course of antibiotics. This heroic experiment brought Marshall notice and the Marshall and Warren infection theory slow acceptance. Starting in 1994, ten years after the first publication of their results, the pair began to be awarded a stream of scientific honours and prizes, culminating in the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 2005. But for over 10 years sufferers from gastric ulcers had been denied an available, effective, cheap and non-invasive cure for their condition [11].

What happened to those experts who for 400 years peddled, and in many cases enforced, false narratives with unshakeable ex-cathedra authority? When new evidence falsified their ideas, did they recant and apologise? No, the majority did not and took their obsolete theories to their graves. As mathematician/physicist Max Planck (inventor of Quantum Theory) cynically observed: “Science progresses one funeral at a time”.

The museum of once-fashionable science. Click for sharper image

American philosopher George Santayana said in 1905: “Those who don’t know the past are condemned to repeat it”. History should teach us caution, but human beings are vulnerable to prophets of doom and each generation breeds its own false narrative. Where our ancestors were cursed by religious orthodoxy masquerading as knowledge, social Darwinism masquerading as genetics, lipophobia masquerading as nutritional advice and old wives’ tales masquerading as gastroenterology, we are cursed by computer-model outputs masquerading as evidence. I speak here of today’s fashionable scientific study, Climate Catastrophism, which, over the last 40 years, has gained great traction by predicting climate apocalypse if we do not mend our evil ways.

In all these cases, the authority and influence of the science elites were, and are, heavily reinforced by the Mathew Effect.

Postscript

As an antidote to the general cynical tone of this post, I am pleased to conclude on a more upbeat note. When considering the inertia in the birth and demise of scientific paradigms, one can argue that things are getting better. Bruno in 1600 was tortured then burnt at the stake for his heliocentric beliefs; Galileo in 1643 was merely shown the instruments of torture. It took 60 years for Galton’s eugenics theory to discredited. It took 50 years for the dietary fat scare to be disproven, but it took only 10 years for Marshall and Warren to disprove the medical dogma on gastric ulcers.

Footnotes

[1] All names in my story of Norman et al. are fictitious.

[2] But 75 years ago, university science departments were not like this. In 1948, physicists Ralph Alpher, George Gamow and Hans Bethe published a paper in the Journal Physics Review. The paper presented the results of Alpher’s PhD Thesis. Bethe (pronounced beta in German) was a friend of Alpher working in another university. Gamow was Alphers’s supervisor. On publication, the name order of the authors was Alpher, Bethe and Gamow – the order of the Greek alphabet. (If they had found a credible researcher named Delter, no doubt he would have been added too). The paper was by all accounts a serious and important contribution to physics but is now universally nicknamed the “alpha-beta-gamma paper”. There is a story I found on the internet that Bethe later regretted participating in this deliberate in-joke and told friends he wished he had been named Zacharia.

[3] I was alerted to the Mathew Effect by reading articles (Natural selection of bad science, Parts I and II) on this subject by John Ridgeway. They were posted in September 2025 on Judith Curry’s blog, Climate etc. (judithcurry.com)

[4] The Mathew Effect in Science. Robert K Merton:1968. Science, Vol 159, No. 3810, pp56-63. https://repo.library.stonybrook.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11401/8044/mertonscience1968.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y Merton bases much of his paper (which he acknowledges) on a 1965 thesis by one of his PhD students, Ann Barrowclough, but she was not included as a co-author.

[5] Merton at this point could, and should, have added to his list – “and money”.

(6) Copernicus himself escaped the attention of the Inquisition by dying (1543) while his book De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium was still in the hands of his Italian publisher. His publisher escaped the attention of the Inquisition by adding a frontispiece to the book explaining that it was a mere mathematical exercise that made no claims to represent reality.

(7) Keys A. 1953. Artherosclerosis – a problem in newer public health. J. Mt Sinai Hospital 20, 118-139

(8) Harvey Levenstein, 2012. Fear of Food: A History of Why We Worry About What We Eat. University of Chicago Press

(9) For a critique of the Keys’ 1953 paper, see Yeryushalmy and Hilleboe. 1956. NY State J Medicine, 1956 (51) pp 118-139.

(10) Hooper L et al. 2012: Reduced or modified fat for preventing cardiovascular disease. Cochran Library: 2012 (5), published by John Wiley.

[11] I know all this because my wife was a life-long sufferer. She was cured by a course of antibiotics in the late 1990s.