Beneath the canopy it is dark and gloomy on the forest floor, the air heavy ahead of late-afternoon rain. I am alone in a remote spot on a remote island in a remote corner of the Pacific. Three men appear from the trees behind me. They are half naked, skin coal black and machetes in their hands. They advance rapidly towards me, swinging weapons and screaming invective. Nowhere for me to run, no help I can call on. I am trapped with bloody death imminent. The first blade sweeps towards my neck…I raise an arm to ward the blow, and …

… wake up in bed sweating and tossing. It’s a nightmare, but a familiar one.

The incident that sparked this trauma took place over 50 years ago.

Five am, Saturday 6th July 1968.

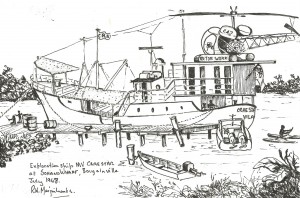

Thirty-six men quietly assemble at the government wharf, near the Provincial capital of Kieta on the southeast coast of Bougainville Island. Most are uniformed and steel-helmeted members of the Royal Papua Niugini Constabulary, all armed with wooden pickaxe handles. An unfit-looking Inspector from Melbourne and a grizzled old Sergeant from Mt Hagen, armed with pump-action shotguns and side arms, lead the uniformed force. In overall charge is a young Australian civilian Patrol Officer, known in Papua Niugini as a “Kiap”. Tied to the wharf behind the group, with its strange profile becoming clearer as the tropical dawn creeps in, is the MV Craestar, a 25 m long exploration ship owned by Conzinc Rio Tinto of Australia[1] Exploration (CRAE). From the ship, three company geologists – armed with geology hammers – join the group. They are Warren Atkinson (the Senior Geologist), Geoff Scott and I. Once assembled, we board open-topped trucks or light four-wheel-drive vehicles and set off along the rutted coast road. We face two hours driving on ever smaller tracks followed by a two-hour march on jungle paths before we arrive at our destination – a village deep in the interior, about 10 km to the SE of the porphyry copper-gold prospect of Panguna, then at advanced feasibility stage.

As you have probably guessed, we were expecting trouble.

The MV Craestar tied to the Government wharf near Kieta on Bougainville Island, June 1968. The ship was a 25m Japanese tuna fishing vessel converted by CRA Exploration into a mobile exploration base by the addition of an assay lab in the hold and a helicopter landing pad and extra cabins at the stern. We liked to think of it as the world’s smallest aircraft carrier. Drawing by author,

The Back Story

That trouble had been brewing for a couple of years. The Panguna deposit was found by CRA in 1964 near the crest of the Crown Prince Range which forms the central spine of Bougainville Island. By 1968, through a massive drilling campaign, CRA had defined a giant open-pitable porphyry copper-gold deposit. The company needed to acquire land for mine, roads, port, and townships. The Australian colonial administration oversaw the land purchases, restricting prices so as not to upset existing stakeholders in the coastal copra industry. Subsistence farmers in and around Panguna thus saw land worth billions of dollars in contained metal value being taken from them and compensation offered based on its value in growing coconuts, the whole issue being exacerbated by long-held political resentment in Bougainville Island to rule from Port Moresby on the PNG mainland.

Underemployed and unsophisticated young men muttered about Bougainville independence and play-trained in the forest with mock wooden rifles. I was told that only a few months before I arrived, a Kiap had been ambushed in a remote jungle area and hacked to death with machetes [2]. Before the 1968 field season, the Australian colonial administration held meetings with village leaders to explain the CRAE stream-sediment sampling program that was planned for that year throughout the island. Most islanders welcomed the incoming exploration team from the Craestar – they wanted a mine to be found in their district that would bring infrastructure and jobs. Throughout Bougainville, this friendliness was our usual experience. Many times, our helicopter could barely take off from the ground by the weight of baskets of local produce (pineapple, citrus, banana, melon, sweet potato, corn) tied to our skids, which we were unable to refuse without giving offence. But in an area of 10-15 km radius around Panguna, many locals resolved that they would repel any incursions by CRA explorers. In the event, we geologists, using a helicopter to leapfrog each other up and down the drainage to collect stream sediment samples, managed to pass through the country so quickly that we were usually gone by the time local villagers were able to organise, or even be aware of our presence on the ground. That is, until…

Friday 5th of July, 1968

On this day, Warren, Geoff, and I landed in some overgrown native gardens near a large village located about 10 km SW of Panguna. Anticipating potential trouble, Warren and Geoff headed off to wet sieve a -80-mesh silt sample from the bank of a small river which flowed past the village. I undertook the safer task – as we thought – of sampling a small tributary stream that flowed in from the jungle. This involved following a forest track that ran along the bank of the stream to collect a sample upstream from its confluence. The track was faint and overgrown, constantly looping away from the stream to bypass fallen trees, thickets of thorn or overgrown gutters. I had to travel at least a kilometer before I found a suitable sample site. As I was kneeling in the stream bed, angry shouts suddenly broke out behind me. Three men stood on the bank, brandishing machetes. Their rapid Pidgin English was beyond my limited command of the language, but their message was very clear, and Anglo-Saxon swear words are a universal language.

No kissim sample long dis pela ples!

Itambu! [3]

Fuck off long Australia!

It was clear they were not happy. I made an exaggerated pantomime of dumping my sample back into the stream, waved my hands in what I hoped were apologetic and deprecatory gestures, and hurried back the way I had come. The men followed close behind, continuing to harangue and swear at me, flicking branches onto the back of my head and shoulders to hurry me along. I thought of the Kiap, hacked to death just a few months before in circumstances very much like my own. If attacked, my geology pick would be a poor defensive weapon. As unobtrusively as I could, I slipped my hand into my shoulder bag and hooked a finger into the ring-pull ignition of a rocket-propelled parachute flare. We always carried a couple of these flares as part of our emergency equipment to signal to the helicopter from the ground: fired vertically, the device ignited and released a rocket that, with impressive noise, smoke, and showers of sparks, shot 100-150 m into the air before releasing a bright magnesium flare to slowly descend on a parachute. I hoped that, fired horizontally, it would create enough confusion and noise for me to escape. A smoke flare would have been better – we usually carried them too, but I had none with me that day. I was not optimistic: fired too early it might escalate a threatened attack into a genuine deadly one; but waiting for a deadly attack would probably be too late. In any case, there was no guarantee that my one-shot horizontal missile, even if I was given the chance to fire it, would have worked as I hoped. Thankfully, although the aggression continued at the same level, I did not have to make that choice. After twenty minutes of pure terror, I made it safely back to the clearing by the main river.

I had been away for over an hour. At the helicopter, Warren, Geoff, and the pilot had been waiting with increasing anxiety for my return. They themselves had not got far, having almost immediately been chased back to the landing site by a large crowd of village men who were now surrounding the helicopter. My three aggressors joined this crowd and added their voices to the cacophony of angry shouts and calls.

We quickly flew off, glad to get away so easily and, in my case, to be still alive.

Once safely landed on the ship at the government wharf, Warren hurried off to Kieta to inform the District Commissioner of what had happened. It was determined that we must go back to the village – this time with police protection. The Commissioner had over 50 riot police housed in nearby barracks at his disposal. They had been flown in at the beginning of the season from New Britain and the PNG mainland for just such an eventuality. Government authority had to be maintained: CRAE had to be seen to take a sample at the site where Warren and Geoff had been repulsed that day. Thankfully, my own sample did not need to be retaken because, although I had made a show of emptying it back into the stream, there was enough fine silt still adhering to the paper sample packet to allow a full suite of assays to be made.

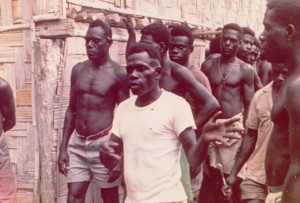

A confrontation near the Panguna Copper prospect between Bougainville villagers and geologists from the MV Craestar. It took place a few days before the incident described in this story. The spokesman in the white T-shirt, probably an agitator from outside the area, spoke good English and is making forceful points about land rights and expropriation. In this instance, we were eventually given grudging permission to collect our samples. The dark skin colour and fine physique are typical of the inhabitants of Bougainville. Photo by author.

The Following day, Saturday 6th July

A long file of armed men climbs steadily into the mountains along a narrow foot track. The Kiap leads, followed by Warren, Geoff, and I, then the Sergeant at the head of his 30 men, many of whom are soon limping due to a recent issue of new boots. The Inspector from Melbourne brings up the rear. As we pass each village, crowds of locals appear: men, women and children, the numbers swelling until at least 200 people are advancing through the jungle and into the hills. Raucous obscenities are shouted, but no one tries to impede our passage – most are obviously just along for the fun: some even cheering us on. After about two hours of steady climbing, the head of our group, consisting of the Kiap, we three geologists, the Sergeant and four of his men (the rest of the police party nowhere to be seen) reach the overgrown gardens beside the river from which we had been evicted the previous day. By this time most of the spectators who had followed us from the coast have melted away, but around two dozen locals, now ominously all men, are waiting for us. Most carry machetes.

“Okay guys” says the Kiap “take your sample now, then we can all go home.”

Warren and Geoff wade into the stream with their sieves and scoop up some silt from its bed. The crowd presses forward, shouting with rage. The Sergeant and his four men try to hold them back, swinging and thrusting with their pickaxe handles. But several men evade the weak cordon, plunge into the stream, and start to wrestle with Warren and Geoff for control of their sieves. The police are badly outnumbered, the Sergeant unslings his shotgun and bloody mayhem threatens. But just at that moment another half dozen police arrive at the top of the ridge overlooking the little valley, and seeing the developing battle below, charge down the hill yelling and swinging their clubs in the manner no doubt instilled in them at the Port Moresby Police Academy. This unexpected flank attack wins the day, and the angry crowd pulls back. All except one – a skinny, white-haired old man – who continues to grapple with Warren for possession of his sieve (he is the one in the white lap-lap on the right of the photo below). The Sergeant promptly arrests and handcuffs him. By the time the remainder of the police contingent – the Inspector from Melbourne still bringing up the rear – trickle in by ones and twos over the next half hour, everything is quiet, and the ex-belligerents and the few remaining spectators are gone. The return march to the coast with our prisoner is uneventful.

Villagers near Panguna copper deposit in Bougainville Island try to stop CRAE geologists Geoff Scott (left) and Warren Atkinson (second from right) from collecting a stream-sediment sample. The guy in the hat is the Kiap. The old man in the white lap-lap (extreme right) is struggling with Warren for control of his sampling sieve. Photo by author.

What Happened Next

The little old man, I was told, was found guilty of civil affray, and sentenced by the magistrate to a week in the Kieta jail.

CRAE successfully completed their geochemical sampling program across the Island. No significant new copper or gold mineralisation was found.

The MV Craestar departed Bougainville and sailed on to conduct similar geochemical exploration programs in the Solomon and Trobriand islands, New Britain, and the north coast of Papua Niugini.

There were more riots and violent protests in 1968 and 1969 before the Australian administration managed to secure a deal with the locals that enabled CRA to proceed with mine construction.

Seven years later (September 1975), Papua New Guinea gained independence from Australia as a separate sovereign nation.

The Panguna mine, through CRA subsidiary Bougainville Copper Limited, operated successfully through the 1970s and 1980s and became a major contributor to the coffers of both the company and the new government of Papua Niugini.

But disquiet over returns to Bougainville from the super profits of the mine and continuing political unrest over Bougainville independence had not gone away. In 1989, the outbreak of the Bougainville Civil War forced Bougainville Copper to precipitously walk away from the mine. Rio Tinto has had no access to the mine site since, which today lies abandoned to the tropical rains.

The now largely forgotten ten-year-long War of Independence that started in Bougainville in 1989 and resulted in around 20,000 deaths (Wikipedia) was much more violent than anything experienced by me more than 50 years ago.

The issue of Bougainville independence is still unresolved.

This article is modified and expanded from a post first published ten years ago in this blog.

[1] In 1996, the company name reverted to Rio Tinto Ltd

[2] I have tried unsuccessfully to verify the tale I was told of the murder of this Kiap. The story may have been apocryphal – the kind often recounted by old hands to scare naïve newcomers. I am more suspicious and cynical now than the young geologist of 1968. But the point is, I believed the story then.

[3] “Itambu” – as they said this, they pointed to an inconspicuous stick which had been stuck in the ground – a marker of some sort. The word “tambu” (as I found out later) means something forbidden or sacred. A taboo. This goes some way towards explaining their extreme anger.