Here’s a geological mystery. The impossible diamond drill hole - a drill hole drilled where no hole could possibly be drilled. I can offer no really satisfactory explanation, although there must of course be one. Perhaps readers can think of one for themselves.

A few years ago I was asked to look at an epithermal gold prospect in a young magmatic arc. The prospect, called Twin Hills[1] , consisted of two adjacent flat-topped hills capped by a horizontal sheet of layered siliceous sinter 3 to 5 meters thick. The sinter was the result of former hot-spring activity in a volcanic area. Chip sampling had yielded anomalous low-level gold values in the outcropping sinter. In drill core the sinter looked like this:

Siliceous sinter seen in HQ core

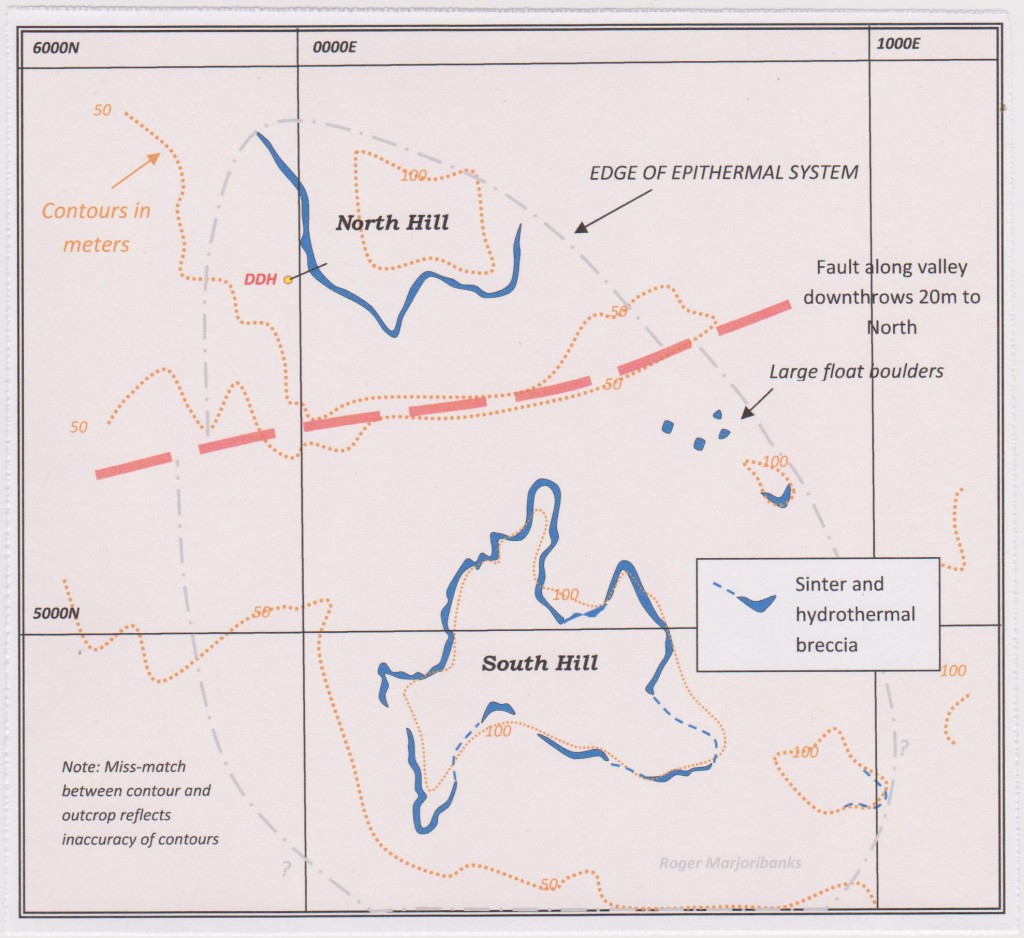

A map of the prospect is shown below.

Geological map of the Twin Hills Prospect

The edge of the sinter formed a rocky scarp around the edge of each hill (coloured blue on the map). The flat-lying ground surrounding the hills was a boulder field of large blocks of sinter that had broken from the scarp and rolled down the precipitous sides of the hills. An abandoned coconut plantation choked with dense secondary tropical growth covered the ground. It looked like this:

Siliceous boulders fallen from the scarp

Several angle DD holes had been drilled by the company to test for a potential gold bearing, steep- dipping feeder zone below the sinter. The position of one of these holes is shown on the map. The hole was certainly drilled and completed a few months before my visit. I saw the core and checked the hole collar in the field (see my photograph, below). I got the impression that the project geologists had never visited the site either during or after drilling. The abandoned site is however a model of good drill-site housekeeping: the collar nicely sealed and capped and concreted in. The hole number is etched on the polythene stand pipe and painted on to a handy adjacent rock.

But wait – that can’t be right…

The impossible diamond drill hole

There is a 20 tonne sinter boulder sitting immediately behind the collar!

There is no way this hole could have been drilled in this position. Therefore the boulder must have arrived after the hole was drilled. But how could a boulder, that must have been derived from the overhanging scarp that lies to the right of the frame (the direction in which the hole was drilled, see map) have positioned itself behind the collar without destroying the collar or even leaving some mark of its passage? On the face of it, the boulder must have arrived here very recently, but it is covered in creepers and appears to have skipped over an ancient fallen log? Let us see…

My first thought was that someone had deliberately placed the boulder in this position – perhaps as a practical joke or to make an environmental protest about exploration activities. But that could hardly be right. In this remote part of the world anti-development Green activists are (thankfully) virtually non-existent and in any case moving a boulder this size would require heavy tracked machinery and there was certainly none of those available either at this remote site.

Maybe the boulder, shaken from the overhanging cliff by some earthquake, rolled down the hill, slowing as it went, just missing the collar, before coming to a stop immediately behind it, and then, with its last few kilojoules of kinetic energy, collapsing sideways to neatly position itself behind the plastic stand pipe.

Maybe then, over the next few weeks, heavy rain and burst of plant growth covered up the scars from the passage of the boulder. In this environment, secondary growth can be rapid.

Maybe then a survey team, sent out to locate and mark the collars of completed holes, arrived and found the side of the massive boulder a handy place to paint the drill hole number.

But there are too many “maybes” in the above argument and they add up to one very unlikely scenario.

So here is another explanation: the drillers (or a site rehabilitation crew) returned to the scene a few weeks after hole completion in order to cement in the hole collar, but were unable to find it again because it was (guess what?) – now covered by a large rock. Not deterred, they decided to play a practical joke on the geologists – cementing in a new dummy drill hole collar as close to the rock as possible, but where no hole could ever have been drilled, and standing back to see if anyone ever noticed?

I dunno. Could be. The facts are as I have stated and illustrated. You now have all the evidence that I have. What do you think?