As a 10-year-old in 1953, I migrated with my family to South Australia, and settled in to one of the fast-growing outer suburbs of Adelaide that were being rapidly built at that time to accommodate the post-war influx of migrants.

I enrolled for the new term at the local Junior School. At least 20% of my classmates were, like me, recent arrivals from Europe. Each morning at school assembly the headmaster, standing in front of the Australian flag and a portrait of the newly crowned Queen Elizabeth, lead us through a recitation that went something like this (I forget the exact words):

I love my country Australia

I love and promise obedience to the Head of Australia, Queen Elizabeth II,

Queen of Australia, Queen of the British Commonwealth and Empire

I promise to obey all her Laws and to be a good citizen.

Migrant assimilation, 1950s style.

On the first morning our teacher (let’s call him Mr. Ford) was anxious to find out the level of knowledge possessed by the new faces in his class and called us one by one to the front to answer questions. Actually, he was anxious to expose our level of ignorance for the titillation of the rest of the class. He was that kind of guy.

Kids whose first language was not English were exposed as being hopeless at English grammar and spelling. Kids who had spent a large part of their lives in a Displaced Person’s Camp in Europe had not mastered all their multiplication tables. A Greek boy called Costas did not know the name of the Australian Prime Minister. A boy from London got a special laugh when it transpired that he had never heard of Don Bradman** even although a framed and signed photograph of said Donald was mounted on the classroom wall below a portrait of the Queen. The poor lad also thought that “footy” was the game played by Arsenal.

I am ashamed to say that I dutifully laughed along with the rest of the class. Anything to be part of the group.

When my turn came to be quizzed, I went to the front feeling fairly confidant. My grammar and spelling were passable, I thought. I had long mastered my multiplication tables (although I had a few problems with the 12x: still do, for that matter). I even knew that Tom Playford was the Premier of the State and Bob Menzies the Prime Minister of Australia.

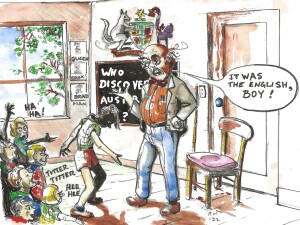

Mr. Ford stood there with legs apart and stomach thrust out, left hand on his hip and right hand expertly rotating a stick of chalk between thumb and forefinger. Full-on schoolteacher performance art as he sought to dominate and intimidate. But he began in an ingratiating tone, eyeing me up and down as he sought my weaknesses.

“Well Roger, you’re from Scotland, eh?”. He said but did not wait for an answer.

“Let’s see what you know about the history of this country. Can you tell me who discovered Australia, Roger?”

He turned to the blackboard and rapidly wrote down the question with loud thumps and squeals of his chalk. Speed writing on a chalkboard is an essential skill for all schoolteachers. None want to turn their back on a class of ten-year-olds for longer than necessary.

As it happened, my father was a history teacher, and ever since I had learned to read, his library of books had been a big source for my reading. Although I did not understand all the big words, there were always plenty of pictures of Kings and Queens, knights in armor, maps and plans of battles, explorers and sailing ships. As a result, I knew a little bit about Australian history, enough at least to recognise this as a trick question. So, I dug deep into my limited stock of knowledge and remembered a picture I had seen of a Captain of the Dutch East India Company nailing a pewter plate to a tree to record his visit to the west coast of Australia in sixteen hundred and something or other *. The context that had stuck in my mind was that these Dutch seamen, trying to reach the fabled Spice Islands of Indonesia with their primitive navigation (and pewter dinner plates), often bumped into Australia instead. I carefully replied…

“Well, um, Sir, um, er. W-was it the D-D-Dutch in, um, ah, sixteen hundred and, ah, s-something?”

A gleam appeared in Mr. Ford’s eye. A gotcha moment. He pounced:

“The Dutch?… THE DUTCH!? … Wherever did you get that idea from?… It was THE ENGLISH!… Haven’t you ever heard of Captain Cook – BOY? … Return to your seat and pay attention, and you might LEARN something”

Even today, after the passage of so many years, I still vividly remember that moment of humiliation. I was mortified, but, looking back, I now know three things with absolute clarity: Mr. Ford knew I was right, he thought I was a smartass and, no matter what I had said, he would have found fault

But the class tittered and tee-heed and laughed sycophantly. I probably deserved that.

As I returned red-faced to my seat Mr. Ford launched into a brief summary of the voyages of Captain Cook.

I wonder what Mr. Ford would have said had I replied that it was the Aboriginal people some fifty Millenia ago? But an answer like that would never have occurred to anyone in 1953.

* Captain Dirk Hartog of the Dutch East India Company, one of the first Europeans to set foot on Australian soil, nailed up an inscribed pewter plate to record his landing on the NW coast of Australia on 26th October 1616. A few decades later, Hartog’s plate was recovered and returned to Holland by another Dutch sea captain and is now on display in Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum. Hartog did not know he was on the edge of a vast unknown continent, but then neither did Captain Cook when he landed on the East coast, 3500 km away and more the 150 years later.

** Sir Donald Bradman was an Australian cricketer of the 1930s and 40s. “The Don” lived in Adelaide in 1953 with near-godlike status.