“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”. George Santayana, 1906

The kilt and distinctive clan tartans are inventions of Englishmen in the early 18th to early 19th centuries. Most people, Scots and English alike, now believe they are the product of an ancient Scottish Celtic culture. Although the Celts lost their rebellions against the British Crown and Parliament in 1715 and 1745, Celtic mythmaking, with English help, eventually conquered the Lowland Scots, the English, and finally the world.

The Invention of the Kilt[1]

“Traditional” Highland Dress - Myth and Reality

More than 70 years ago, my father (an Edinburgh historian and teacher) told me this story – it’s an old Edinburg joke that probably dates back to the 1920s when he too was a lad:

“If a Londoner sees a man in a kilt, they think he’s a Scotchman. In Edinburgh, if they see a man in a kilt, they think he’s a Highlander. In the Highlands, however, if they see a man in a kilt they know he’s an Englishman.”

Alas, how things have changed. Travel to Scotland today (as I did earlier this year) you will be welcomed at the border by a person (a woman on this occasion) playing the bagpipes in full highland regalia (ghillie brogues, knee-high hose with tassels, sgian-dubh, tartan kilt, hairy sporran over crotch, jacket with silver buttons and cairngorm brooch, shoulder plaid and glengarry hat with pom-pom and feather). Continuing to the capital Edinburgh, your ears are assailed on every corner of Princes Street by more kilted persons playing medleys of Scottish tunes. I spotted a tour guide from Germany dressed in tartan kilt and sporran (what clan did he belong to?). In the Royal mile there was a bare-chested man in a kilt with his face painted blue – I think he was channeling Mel Gibson in that wildly-inaccurate 1995 Hollywood Movie Braveheart. It seemed that every second or third shop was offering to kit you out in your own personal clan tartan. Even in the Highlands itself, you can’t always get away from the tourist shtick.

****

Edinburgh Retail Interlude:

“Guten Morgen. Herr Schmidt, from Dusseldorf, ja? – yes, one moment sir… (he types on his computer) – here it is, we do have a tartan for you, sir – it is the ancient dress tartan of the McHaggis of Invercreagh. A Herr Schmidt from Heidelberg was here – yes, yes, yes, in this very shop sir – in… aah… 2003 – and he assured us that his great-great grandfather married a lass from the McHaggis clan in 1876″ – We have very strict standards in this establishment, you know – but you most definitely do qualify sir”.

****

Lowlanders make up more than 80% of the Scottish population and have mostly Anglo-Saxon, Anglo-Norman, Welsh or Irish roots. Prior to the late 18th Century, Lowlanders almost universally regarded Celtic Highlanders as half-naked savages living in primitive conditions outside of normal, law-abiding, civilised society. They were not wrong.

The few available accounts of the dress of Highlanders before the mid-to-late 18th century describe (in some cases with wood-cut illustrations) a single long length of hand-woven woolen cloth called a plaid, woven in a cross-banded pattern called tartan[2]. Hand spinning and weaving were then a scattered cottage industry throughout the Highlands and Islands. The plaid was worn over the shoulder to hang fore-and-aft to mid-thigh and secured at the waist by a belt. Below the waist, the plaid was arranged to form a sort of open-sided mini-skirt. Excess material could be draped over the head and shoulders like a shawl or hoodie or bundled around the waist like a shed pullover. In short, a cheap, one-piece, multi-purpose garment, useable for many things, but not the most efficient at any. The wealthy few might wear a woolen or linen shift below the plaid. The even wealthier few (i.e. Clan Chiefs) scorned the peasant dress and wore tartan trousers called trews (or trowse).

Following the failed Jacobite rebellion of 1715, English Regiments were stationed in the West Highlands at Fort William and in the East at Inverness. The Army built new roads and tried to suppress inter-clan fighting and ensure safety for travelers.

The early 18th century was the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution in England. Thomas Rawlinson (1669-1737) was a member of a family of Quaker Ironmasters who owned and operated a number of open-hearth furnaces in Lancashire and Chesire. They used hematite ore from nearby mines and reduced it to iron with charcoal. The ore was plentiful, but wood for making the charcoal was not. Around 1725, Rawlinson travelled to the now quasi-pacified Highlands to seek fresh charcoal supplies. His eyes were on the virgin birch forests of Invergarry, north of Inverness [3]. These were owned by Ian McDonnell, Clan Chief of the McDonnells of Glengarry. Rawlinson and The McDonnell formed a partnership. The Chief would lease access to his forests and provide labour from his serfs. Rawlinson would ship iron ore from England to Glengarry and build an iron smelter there; for their return journey, his ships would load charcoal for England. A synergistic and mutually profitable arrangement, they hoped. Representing his family, Rawlinson moved to live in Glengarry (he rebuilt Invergarry castle, destroyed by the Army after the 1715 Jacobite rebellion) and became Managing Director of the enterprise.

Rawlinson soon realised that the half-naked dress of his new employees was unsuitable for industrial operations, whether felling trees, making charcoal or attending to open-hearth iron furnaces. For Rawlinson it was a Health and Safety issue, but the garb also offended his English Quaker sensibilities. So, around 1727, he approached the tailor of the English Redcoat Regiment stationed in nearby Inverness and together they devised a suitable industrial dress for his employees. This was a separate, belted, mid-knee length tartan skirt in plaid material featuring multiple stitched-down pleats to keep it heavy and weighted. They called this garment a kilt. Both Rawlinson and the Chief wore the new dress, and its obvious practical advantages soon made it widely popular.

In 1725, with interclan fighting and disorder still rife in the Highlands, the English authorities raised an armed militia (then called a watch), to help keep Law and Order. The Watch drew its recruits from Highland clans that had been loyal to the crown during the 1715 Jacobite rebellion. These recruits were mainly Cambells, but also included Grants, Frasers and Munros. They were outfitted with a uniform of a one-piece belted plaid (12 yards long!) in a distinctive dark tartan of forest green and navy-blue. This quickly led to their nickname the Black Watch (in Gaelic: Am Freiceadan Dubh).

For a different explanation of this nickname, and the subsequent history of the Black Watch and other Highland Regiments, see footnote [4].

The presence of the Watch created the beginnings of the idea that groups of Highlanders could be identified by a common tartan pattern. In 1739, the Black Watch Militia was converted to a line Regiment and their plaid replaced by a kilt, topped with the red jacket with contrasting regimental facings of the British soldier.

The Invention of Clan Tartans

In 1822, the brothers John and Charles Allen[5] appeared in Edinburgh. They were born and raised in southern England from an English naval family (their grandfather was an Admiral, their father a naval Lieutenant), but nothing of their early life is known. Somehow, by the time they were young adults, they had acquired a fascination for and a knowledge of Gaelic and Celtic myth and legend. For many years before their arrival in Edinburgh, they appear to have been corresponding with major Scottish tartan retailers. These were now commercial firms concentrated in centers close to the Highlands, like Stirling. The Allens provided them with “traditional” designs that the brothers, when later challenged, would claim to be based on an ancient, illustrated text in their possession – a document (they claimed) given to one of their ancestors by Bonnie Prince Charlie no less [6]. Among their many talents, the Allens obviously had a flair for textile design. Of course, no one ever got to see the original of this ancient family document. Sir Walter Scott asked, but was fobbed off with elaborate and ingenious excuses. The designs, along with elaborate and fanciful stories of their origins and how they came to be in the possession of the Allen family were eventually published by them as Vestiarium Scotticum” (1842) and later as “Costume of the Clans” (1845). These lavish, limited-edition, books, with their multiple hand-coloured plates, became a major source of tartan designs throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

1822 marked the visit to Edinburgh of the Hanoverian King George IV. This was a big and lavish event: the first visit of a British monarch to Scotland for almost 200 years. The event organiser, romantic novelist Sir Walter Scott, requested that all Highlands clan chiefs to come to Edinburgh to meet the King. Each was to bring a number of retainers identically dressed in a kilt of a distinctive tartan, so that so that the elderly King could tell which clan was which. The Chiefs, enthused by their new-found status, hurried off to the Stirling tartan emporiums to choose tartan designs from their pattern books. These patterns were mostly the creations of, or inspired by, the Allen brothers.

Edinburgh was full of tartaned, kilted Highlanders. The King was charmed and ordered for himself a kilt in Royal Stuart tartan (bright red, white. yellow and blue industrial colours: you can Google a portrait of the portly Hanoverian in this outfit).

The extravaganza was a great success. The Celts had finally conquered Scotland, and England too. Their sartorial revenge for the battle of Culloden in 1745. Later, these concocted Celtic myths were to conquer the British diaspora around the World as well. Every Highlander, Lowlander, or Englishman with a Scottish surname, or a hint of Scottish blood in their ancestry can now choose their very own “traditional” tartan [7].

Death charge of the Highlanders: the Battle of Culloden, 1745

Death charge of the Highlanders: the Battle of Culloden, 1745

Queen Victoria and her Consort Prince Albert fell in love with the Highlands during a visit to Scotland in 1843, They bought an estate near Braemar in the Dee valley of Perthshire where, in 1848, they built Balmoral Castle – a vast, granite-built, neo-gothic mish-mash of castellations, Romanesque arches, pointy (and pointless) turrets, faux arrow loops and Juliette balconies: the interior filled with Victorian-Gothic-Celtic-tartan kitsch. There Victoria and her husband would spend their summer holidays and Albert could stalk deer in his kilt without appearing too ridiculous. A tradition the Royal Family has maintained to this day.

With Victoria and Albert as an example, wealthy upper-class Englishmen (and not a few Lowlanders) flocked to the Highlands to buy similar estates where they could act the role of Clan Chiefs and slaughter the local wildlife (bigger, more numerous and much wilder than anything available in England). They bought land, as Victoria had done, from Clan Chiefs eager to sell out their tenants for a dollop of cash. The English aristocracy pretended to be Clan Chiefs: The Clan Chiefs pretended to be English aristocracy. The local subsistence population (whose presence with their sheep and cattle would have restricted the field of fire) had their tenancies revoked and forced to move out. Single young men flocked to the local Highland Regiment recruitment centers; others sought employment in the rapidly-industrialising Lowland cities. A huge number emigrated to the United States or the Colonies. The Highlands became depopulated and remain so this day, an event known as the Highland Clearances.

Final Thoughts

There are no real villains in this story. Thomas Rawlinson brought jobs and money to an impoverished Highland community and had concerns for his workers’ physical and moral safety. John and Charles Allen made little or no money from their fantastical schemes and got no royalties on their designs. More charming, deluded eccentrics than fraudsters, they lived on the charity of friends and died in genteel poverty in the late 1870s, still researching their imaginary roots. The Celtic myths they helped promote were harmless and amusing stories that give all Scots a sense of Nationhood and a glorious, romantic past.

Tartan patterns are genuine Highland inventions that reflect the artistic genius of the Celts.

Victoria and Albert, playing at dressing up in their Highland Estate, were hardworking Royals who deserved their summer holiday fun.

The “traditional” Highland dress, for all its dubious origins, is still a fine and impressive dress for a man.

Looking even further back in time

My tale of Scottish myths and legends almost exactly mirrors how, around the 13th century, the Anglo-Norman ruling aristocracy of England adopted the Celtic myths of Wales, Cornwall and Brittany – the legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table - as the true history of their own inheritance.

This is an example of the process to which the quote at the head of the post refers.

Acknowledgments

My content, as well as its title, is taken from the book: The Invention of Scotland: Myth and History, by Oxford historian Hugh Trevor-Roper. Specifically, Part III: The Sartorial Myth. Trevor-Ropers’ book was published by Yale University Press and printed by Cambridge University Press in 2006.

It is a meticulous scholarly work with full documentation and references and written an easy and readable style.

Extra details have been added from my internet searches.

The words, commentary, opinions and illustrations are mine.

*****

Personal Note:

This post was prompted by nostalgic feelings for Scotland as it was when I was a lad more than 70 years ago. But would I really want to live back then with no fridge in the kitchen, no washing machine in the laundry, no TV in the lounge, no computer in the office and no car in the garage? Definitely not.

******

[1] According to the dictionary, Kilt is a Middle-English word of Scandinavian origin derived from the verb kilten which means to fold or pleat fabric. Gaelic speakers (perhaps mockingly) called the garment a philibeg or little skirt. The Gaelic usage soon fell into disuse.

[2] The generic tartan pattern seems to be a genuine Highland original. It was achieved by weaving with different wool threads in muted vegetable-dyed colours of brown, green, russet and blue. It provided good camouflage for stalking deer (or men) on open heather moors.

[4] Or, more plausibly, the nickname referred to the black hearts of those who would fight for the English.

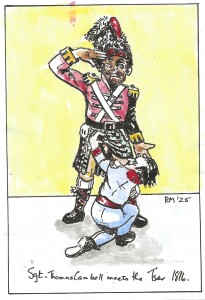

In 1739, the British Army raised several Highland Regiments, one of them the former militia group called the Black Watch. Each Regiment was uniformed in a kilt of distinctive tartan. When the second Jacobite rebellion of 1745 took place, the Highland Regiments were away fighting the French in Flanders, which probably explains why Prince Charles Edward Stuart had such easy early success. Through Colonial, Napoleonic and World Wars, the Highland Regiments gained a reputation for their fighting spirit. After the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, kilted Highland Regiments were part of the Allied occupation forces in Paris. Sergeant Thomas Cambell of the Kings Own Cameron Highlanders (the 79th Regiment) recalls in his memoirs being summoned to the Elysée Palace to meet Tsar Alexander I of Russia at for a detailed inspection of his uniform:

“He examined hose, gaiters, legs, and pinched my skin, thinking I wore something under my kilt, and had the curiosity to lift my kilt up to the navel, so that he might not be deceived”

The Tzar of Russia inspects the kit of Sergeant Thomas Cambell of the 79th Highland Regiment. The Elysee Palace, 17th August 1815,

How nice to be a Tzar. How nice to humiliate a common soldier for your own gratification and think nothing of it.

(Details on the Black Watch, Highlands Regiments and Sgt. Thomas Cambell from www.highlandsmuseum.com; www.theblackwatch.co.uk and https://the79thcameronhighlanders.co.uk/regimental-history).

[5] Over the course of the next 20 years, the Allen brothers progressively “Scottified” their surnames. First to Hay-Allan (Allan is the Scottish form of Allen), then to Stuart-Allan and finally to Sobieski-Stuart – inventing new genealogies for themselves along the way, supported by ingenious argument and (more) secret documents. Ultimately, the brothers claimed to be the legitimate grandsons of Bonnie Prince Charlie (through a secret marriage to a Polish Princess), making the elder brother King John II of England (and John I of Scotland), and his younger brother Charles, the Prince of Wales. At the time, many of the Celtic elite of Scotland went along with this nonsense and supported the brothers’ lifestyle.

[6] Charles Edward Stuart, grandson of James II of England (and James VI of Scotland), known as the “Young Pretender” to the British throne. He died in 1788 without issue. The “Old Pretender ” was his father, James Frances Edward Suart, son the deposed James II, who led the 1715 Jacobite rebellion.