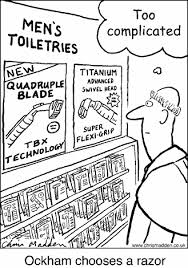

William of Occam (or Ockham) was a 14th century English Franciscan monk and philosopher who gave his name to the principal now known as Occam’s razor. This is a well known philosophical principle that has universal application in all fields of problem solving. It states that, given a range of possible solutions, the simplest solution – that is to say, the one that rests on the fewest assumptions – is always to be preferred. For this reason the maxim is often referred to as the principle of economy, or even, with more impact, as the KISS principle (Keep It Simple, Stupid). However, Occam’s razor – conjuring up an image of a ruthless slicing away of over complex and uncontrolled ideas – has a certain cachet which the other terms don’t quite capture.

All stages of mineral exploration involve making decisions based on inadequate data. To overcome this, assumptions have to be made and hypotheses constructed to guide decision making. Applying Occam’s razor is an important guiding principle for this process, and one that every explorationist should apply. This is especially true when selecting areas for exploration, and in all the processes which that entails, such as literature search and regional and semi-regional geological, geochemical and geophysical mapping. However, as the exploration process moves progressively closer to a potential orebody – from region to project to prospect to target drilling – the successful explorationist has to be prepared to abandon the principle of economy. The reason for this is that ore bodies are inherently unlikely objects that are the result of unusual combinations of geological factors. If this were not so, then metals would be cheap and plentiful and you and I would be working in some other profession.

When interpreting the geology of a mineral prospect, the aim is to identify positions where ore bodies might occur and to target them with a drilling program. Almost always, a number of different geological interpretations of the available data are possible. Interpretations that provide a target for drilling should always be preferred over interpretations that yield no targets, even although the latter might actually represent a more likely scenario, or better satisfies Occam. However, this is not a licence for interpretation to be driven by mere wish-fulfilment. All interpretations of geology still have to be feasible, that is, it they must satisfy the rules of geology. There still has to be at least some geological evidence or a logically valid reasoning process behind each assumption of the model that leads to defining the drill target. If unit A is younger than unit B in one part of an area, it cannot become older in another; beds do not appear or disappear, thicken or thin without some geological explanation; if two faults cross, one must displace the other; faults of varying orientation cannot be simply invented so as to solve each detail of complexity. And so on.

There comes a point in any exploration program when it is easy to find any number of good reasons why the property might not contain an ore body. Managers worried about budgets, rival explorationists who want your share of the exploration dollar or your own internal self-doubt and lack of confidence can all people this list of fools and Jeremiahs, and the logic of Occam’s Razor may well be on their side.. But remember, the skill of the experienced explorationist lies in finding the one good reason why there might still be an ore body to be found, and long odds against discovery are always the nature of the game.