The philanthropist of Nullagine

“The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” – L P Hartley

The town of Nullagine, in the Pilbara region in the northwest of Western Australia, is situated 1400 km NNE of the State capital Perth, where the old Great Northern Highway crosses the broad, dry, sandy bed of the Nullagine River. The town was established following gold discovery there in 1886 and rapidly grew to a bustling centre with 3 pubs, 12 stores and a population of over 3000. With eight multi-head stamp batteries operating in and around town, the noise must have been constant and deafening.

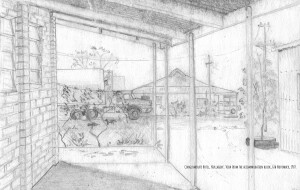

Click for larger image.

That was 1914. Fifty years ago, almost halfway between then and now, I was based in Nullagine for 5 months over the summer of 1969-1970. Fifty years ago, the Great Northern Highway still passed through the town – after 600 hellish kilometers of corrugated dirt road from Meekatharra. The population had dwindled to around 200 – most of these members of the indigenous Martu tribe camping in the riverbed outside town. There was a single pub, a store, Shire Office and Depot, police post, nursing clinic and junior school. There was a branch of the Country Women’s Association (CWA). The pub: a single Storey corrugated iron building with a wide veranda out front. It was, and still is, called The Conglomerate Hotel, built, and named, after the discovery and exploitation of nearby conglomerate-hosted palaeoplacer gold which stimulated, for a few years in the nineteen thirties, a temporary revival of the pre-WW1 glory days of Nullagine. With an ounce of gold in 1969 fetching around $40, there was little remaining interest in the precious metal, save by a few old prospectors who lived in bush camps outside town and walked in, pushing a wheelbarrow, every couple of weeks (pension day) for supplies and a session at the bar. The barman at the Conglomerate would often accept gold dust and nuggets in payment of bar bills and, by the end of my stay in Nullagine, had two full jam jars on a shelf below the bar. He had no idea what this was worth, but in spite of the depressed gold price of 1969, I have no doubt he was well ahead.

The Conglomerate Hotel in 1969. Click for a sharper image

I got to know one of these old prospectors quite well. He was called Otto and had a fascinating life story. According to him, he was born in Saxony towards the end of the nineteenth century and was conscripted by the German Army to fight in the trenches during the last years of the First World War. Surviving the slaughter of that war, he was recruited by the British in 1919 (along with many thousands of other ex-combatants), to serve under British General Ironside against the Red Army in European Russia. On the withdrawal of the allied forces, Otto stayed on to fight for the White Russians in the Urals and Siberia. With the collapse of anti-Bolshevik resistance in 1922, Otto found himself stranded in Central Asia and, with several companions in the same plight, walked the length of the trans-Siberia rail line to Vladivostok in the Soviet far east. There he became a merchant seaman and sailed the world for several years. In the Great Depression of the early 1930’s, his ship laid up in Fremantle for want of cargo, Otto jumped ship and walked to Nullagine to become a gold miner. There he stayed, never once leaving the Pilbara.

The turn of the decade from 1969 to 1970 was arguably the height – the peak madness – of the nickel boom – a speculative stock market bubble inspired by the success of the small company Poseidon whose shares had soared from to less than 20c in early 1969 to almost $283 by February 1971 following a nickel sulphide discovery at Windarra in the Western Australian Yilgarn. The company I worked for at that time owned a Mining Lease in the barren spinifex covered hills 25 km north of Nullagine that briefly was one of the “hot” nickel exploration properties. The claim contained a belt of outcropping ultramafic rocks which countless millennia of weathering had converted to a spectacular siliceous cap, coloured beige, apple-green and iridescent black by secondary minerals of iron, chrome, nickel and manganese. Some of this cap was gem-quality chrysoprase, veined with tiger’s eye (see picture). Selected rock-chip samples gave extremely high nickel assays, ranging up to 14%. Chrysoprase is chalcedonic quartz stained green by secondary nickel minerals, but we knew very little about nickel geochemistry in these days (certainly, I didn’t), and we had carried out an Induced Polarization (IP) survey which our consultant geophysicist had interpreted as showing a distinct anomaly, whose only possible causation (he wrote in his report, before collecting his fee) was the presence of a massive sulphide body at depth. We had a drill target!

Chrysoprase veined with Tiger’s Eye, magnesite, and iridescent black hematite. The specimen was collected from a siliceous weathering cap developed on serpentinised peridotite cut by crocidolite-asbestos veins. Location approximately 25 km NNE Nullagine, Western Australia. Picture frame covers 15 x 10 cm. Click for a sharper image.

Naturally, all this was reported to the stock exchange. Shares in the company soared and, in the febrile atmosphere of 1969, we were being noticed, and not just in our small Western Australian Pond.

BLUE SKY MINES N.L. TO COLLAR FIRST HOLE INTO HOT PILBARA PROPERTY!

In January we collared our first hole on top of a rocky hill with a wide view of the surrounding country. Distant plumes of lingering dust marked the passage of vehicles on the highway to the west. One afternoon, with a shade temperature in the low forties (that is: a fairly cool day for the Pilbara in January), I was logging core under an awning when a Land Rover pulled off the highway and followed the track to the site. At the foot of the hill, two men got out. They were dressed in baggy shorts, colourful shirts and wide straw hats: their limbs paper white. They took a large box from the back of their vehicle and carried it between them as they climbed the hill towards us. Jeez, said the driller, they gotta be poms just off the boat. And so it proved. They were scouts working for a group of English stockbrokers and had flown out of London only 5 days before. The “box” was an insulated container – an Esky – full of ice and beer. With such offerings they were of course welcome, and although at this passage of time I cannot recall what wild and exaggerated stories the drillers and I spun them as we drank their beer up there on the hill, they got their own back later that night at the hotel by winning $5 dollars off me in a game of darts.

Old Mrs. Howard was the matriarch of Nullagine. She owned and operated the store/Post Office. She owned the Conglomerate Hotel. She was the head of the local branch of the Country Woman’s Association. The CWA owned a house in town where members who lived in distant cattle stations scattered across the vast Nullagine Shire could stay when they came to town to buy supplies. In 1969, the CWA wanted to raise money to upgrade this property and had prepared a large cardboard cut-out thermometer with a scale marked off in $100 increments all the way up to their target sum of $1000. This was prominently labelled CWA House Appeal and nailed high on the wall behind the bar of the pub. Donations would be recorded by a rising red line with the name of the donor written opposite each significant jump in the column. This thermometer was in place by early November.

In Australia each year, on the first Tuesday of November, activity stops as people crowd round the radio or TV to watch the Melbourne Cup horse race. Billions are wagered with bookies; thousands of sweeps are run in offices and pubs. Nullagine followed the tradition in 1969 with a raffle in the pub the night before the race: we paid $2 each to draw the name of a horse from a hat. After the running of the race, the owner of the winning horse would collect all the money after small consolation sums were paid to the owners of the 2nd and 3rd placegetters. That Tuesday I came back to town late after a hard day in the field to find the post-race party in full swing. I held the winning ticket! Fifty dollars was pressed into my hand: I gave it to Ted the barman and told him all drinks were free. Then another round followed, then another, then another. I think by this stage Ted must have been paying for the drinks from his secret jam-jar fund, or perhaps (more likely) Mrs. Howard had given him the nod. Mrs. Howard approached me and said -

We ladies in the CWA all agreed that if any of us won the cup we would put our winnings into the CWA house appeal.

So, I said – Sure, great cause – and gave her two twenties and a ten from my wallet. To a great cheer from the crowd, Ted got out a stepladder and, with a fine brush and pot of paint, filled in a short red line at the bottom of the cardboard thermometer. Then, using the same brush, he carefully wrote my name beside it:

Roger Marjoribanks – $50

(In a previous life, Ted had been a house painter by profession so was used to working with paint pot and brush atop a ladder).

The Conglomerate Hotel, Nullagine today. Essentially unchanged since 1969 although the candy-stripe roof with its large air-conditioners and the collection of old mine junk in the forecourt, are new additions. Few travelers ever drive past the Conglomerate without stopping for a “coldie”.

Click for a sharper image.

The world rolled on. Four diamond drill holes were completed on our “hot” property north of Nullagine and showed it to be a complete dud – the IP anomaly happily explained, ex post-factum, by the consultant geophysicist as being caused by magnetite concentrations in the bedrock. I left town and moved on to other projects. The market bubble in nickel shares burst, as all bubbles do. Shares in Poseidon Nickel N.L. collapsed to $140 by March 1970 and continued south.

It was five or six years before I passed through Nullagine again and fronted the bar at the Conglomerate Hotel to book a room for the night. The familiar environment of the old pub was unchanged, but there were no faces that I recognised either behind or in front of the bar. As I signed my name on the register, the barman leaned over:

You’re Roger Marjoribanks? –

he asked. I assured him that I was.

The Roger Marjoribanks?

I answered that, as far as I knew, I was the only one.

You are famous around here mate, he said, and pointed to the wall behind the bar where the now yellowing and fly-specked money thermometer from 1969 was still nailed. For whatever reasons it had never been taken down or any further donations recorded. Perhaps they had mislaid the stepladder? And it recorded, against a tiny initial rise in the mercury, the name of the sole apparent contributor to the CWA house fund, still legible after all these years:

Roger Marjoribanks – $50

The barman told me that for all the years he had worked in Nullagine, drinkers at the bar had speculated as to who this solitary benefactor of the Country Woman’s Association could be. I had become the mysterious Philanthropist of Nullagine.

But it did not even get me a free beer.