In the grey light of a tropical dawn on 6th July 1968, fifty men assembled at the government wharf, Sohano, on the south coast of Bougainville Island. They were members of the Royal Papua Nugini Constabulary, and they were armed with long wooden pick-axe handles. An inspector from Melbourne and a sergeant from Mt Hagen, with shotgun and side arms, led the uniformed force. In overall charge was a young Australian civilian Patrol Officer, known in PNG as a “Kiap”. Tied to the wharf behind the group, with its bizarre outlines becoming clearer as the sun slowly rose, was the MV Craestar, a 30 m exploration ship owned by Conzinc Rio Tinto of Australia Exploration (CRAE). From the Craestar, three company geologists in high-visibility vests and armed with geology hammers and -80 mesh sampling sieves joined the police group. By the time the sun had hauled above the horizon, all had boarded open-topped trucks or light four-wheel-drive vehicles and were bouncing along the rutted coast road. They faced two hours driving on ever smaller tracks followed by a two hour trek along jungle paths before they arrived at their destination – a group of villages deep in the interior, about 10 km SE of the CRAE copper-gold prospect of Panguna, then at advanced feasibility stage. They were expecting trouble.

The MV Craestar anchored off Bougainville Island in early 1968. The ship, owned by CRA Exploration, was converted from a Japanese tuna fishing vessel into an exploration ship by the addition of an assay lab in the fish hold and a helicopter landing pad at the stern. Between 1967 and 1970, the ship was used extensively as a base for mineral exploration programs in the Solomon and Trobriand Islands and along the coastal belts of Papua Nugini.

That trouble had been brewing for a couple of years. Exploration at Panguna on the crest of the Crown Prince range in the centre of Bougainville Island had defined a massive open-pittable porphyry copper-gold deposit. CRA needed to acquire land for mine, roads, port and townships. The Australian colonial administration oversaw the land purchases, restricting prices so as not to upset existing stakeholders in the coastal copra industry. Subsistence farmers in and around Panguna thus saw land worth billions of dollars in contained metal value being taken from them and compensation offered based on its value in growing coconuts, the whole issue being exacerbated by long-held political resentment to rule from Port Moresby in the PNG mainland. Underemployed and unsophisticated young men muttered about Bougainville independence and play-trained in the forest with wooden mock rifles. A Kiap was ambushed and hacked to death with machetes. Before the 1968 field season the Australian administration had held meetings throughout the island to explain the planned CRA stream-sediment sampling program for that year. In fact, the overwhelming majority of islanders welcomed the incoming exploration team from the Craestar – they wanted a mine in their district to bring infrastructure and jobs. But in an area of 10-15 km around Panguna, many locals resolved that they would repel any incursions by CRA explorers. In the event, geologists, using a helicopter to leapfrog each other up and down the drainage to collect their stream sediment samples, passed through the country so quickly that they were usually gone by the time most locals were aware of their presence.

That is, until the 5th of July. On that day, the Craestar geologists – Warren Atkinson, Jeff Scott and the author of this Post – landed in some overgrown gardens a few hundred meters from a village about 10 km SE of Panguna. Anticipating potential trouble, Warren and Jeff headed off to wet sieve a silt sample from the bed of a river which flowed past the village. I took a faint forest track along the bank of a small tributary stream to collect a sample upstream from the main drainage. I had to go further than I anticipated – about 2 km – but eventually found a suitable site and was kneeling in the stream bed when I was startled by loud shouts behind me. Three young men stood there, all brandishing long and wicked looking machetes. Their Pidgin English was mostly too rapid for me to understand, but Anglo-Saxon swear words are a universal language. It was clear they were not happy. Abandoning my sample to the stream, I picked up my shoulder bag and hurried off the way I had come. The men followed close behind, shouting, swearing and flicking small branches onto the back of my head to hurry me along. I thought of the Kiap, hacked to death in Bougainville just a few months before in circumstances terribly like my own. If attacked, my geology pick would be an ineffective defensive weapon, so as unobtrusively as I could, I slipped my hand into my bag and hooked a finger into the ring pull ignition of a Parachute Flare. We always carried a few of these flares as part of our emergency equipment to signal to the helicopter from the ground; fired vertically, the device released a rocket that, with impressive noise, smoke and sparks, shot 200 m into the air before releasing a magnesium flare that descended slowly on a parachute. I hoped that, fired horizontally, it would create enough confusion and noise for me to escape. This gave me some small comfort at the time, but it probably would not have saved me. In all probability, my one shot, non-lethal missile could have turned a limited attack into a lethal one. Thankfully, I did not have to use it. It took me fifteen minutes to get back to the helicopter. The longest fifteen minutes of my life.

At the helicopter, Warren, Jeff and the pilot were waiting with increasing anxiety for my return. They themselves had not got far, having being almost immediately chased back to the landing site by a large crowd of villagers – men, women and children – who were now surrounding the chopper. We quickly flew off, glad to be still alive.

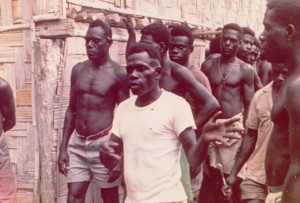

Angry Bougainville villagers confront CRA exploration geologists near Panguna Copper mine in 1968 and demand they “No kissim sample long dispela ples” and “fuck off long Australia”. The indigenous inhabitants of Bougainville are ethnically, racially, linguistically and geographically distinct from Melanesians of the PNG mainland. The very dark skin colour is characteristic.

So on Saturday 6th July the long procession steadily climbed into the mountains along a narrow track through the jungle. The Kiap led, followed by the three Craestar geologists, then the Sergeant at the head of his 50 men, many of whom were soon limping due to a recent issue of new boots. The inspector brought up the rear. Crowds of locals began to appear: men, women and children, the numbers swelling as the march wore on until at least 200 people were advancing into the hills. Raucous obscenities were shouted, but none tried to impede passage – most were obviously just along for the fun. After about two hours the head of the group, consisting of the Kiap, the geologists, the Sergeant and four of his men (the rest of the police party nowhere to be seen) reached the overgrown gardens beside the stream where the geologists had been chased away the day before. About a fifty villagers, now ominously all men, were waiting for them. “Okay guys, take your sample now”, said the Kiap to the geologists, “then we can all go home”. Warren and Jeff waded into the stream with their sieves and scooped up some silt from its bed. There was a yell of anger from the crowd which pressed forward – the sergeant and his men tried to hold them back, swinging their pick-axe handles like broad swords, but several men broke free from the crowd and started to wrestle with the geologists in the stream for control of their sieves. It was an unequal contest and bloody mayhem threatened: but just at that moment another half dozen policemen arrived at the top of the ridge overlooking the little valley, and seeing the battle below came charging down the hill yelling and swinging their clubs in the manner no doubt instilled in them at the Port Moresby Police Academy. This unexpected flank attack won the day and the crowd pulled back. All except one – a skinny, white-haired old man who continued to wrestle for possession of a sieve (he is the one in the white lap-lap on the right in the photo below). The sergeant promptly arrested and handcuffed him. By the time the rest of the police contingent – the Melbourne Inspector still bringing up the rear – had trickled in by ones and twos over the next half hour, everything was quiet, and most of the ex-belligerents and spectators had melted away. The return journey to the coast was uneventful. The little old man, I believe, got a week in the Kieta jail for affray.

Villagers near Panguna copper deposit in Bougainville Island try to stop CRA geologists from collecting a stream-sediment sample. The geologists (wearing orange hi-vis jackets) are Jeff Scott at left and Warren Atkinson at right. The guy wearing the Akubra hat is the Kiap. The third geologist with the party (me) is hanging back, trying to keep out of harm’s way (and taking photographs).

Villagers near Panguna copper deposit in Bougainville Island try to stop CRA geologists from collecting a stream-sediment sample. The geologists (wearing orange hi-vis jackets) are Jeff Scott at left and Warren Atkinson at right. The guy wearing the Akubra hat is the Kiap. The third geologist with the party (me) is hanging back, trying to keep out of harm’s way (and taking photographs).

There were more riots and civil affrays in Bougainville in 1968 and 1969 before the Australian administration managed to secure a deal with the locals that enabled CRA to proceed with mine construction. The Panguna copper mine operated successfully through the 1970s and 1980s and became a massive contributor to the PNG economy. But disquiet over returns to Bougainville from the super profits of the mine, and political unrest over Bougainville independence did not go away, and in 1989 CRA was forced to abandon the mine by the outbreak of the Bougainville Civil War. CRA has had no access to the mine site since , which today lies abandoned to the tropical rains.

The Civil War that started in Bougainville in 1989 and lasted for almost a decade was much more violent than anything experienced by the author 45 years ago and lead to the deaths of many thousands of people. The little known conflict is the setting for ‘Mr Pip” a recently released NZ film starring Hugh Laurie.

very good website congratulations my name hugo