FEAR OF FAT

Men, it has been well said, think in herds; it will be seen that they go mad in herds; while they only recover their senses one by one. Charles Mackay, 1841

In 1841, Scottish journalist Charles Mackay wrote a book called Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. The title is self-explanatory, the book became a classic, still in print today.

Mackay’s examples are drawn from the corruption of religion and capitalism, but today’s crowd madness is more likely to be the result of the corruption of a different source of secular authority – Science. If Charles Mackay were to return today, he would not lack material for additional chapters to his book. The obvious chapter would undoubtedly be about the Global Warming Scare (1) of the 21st century, but it is too soon to write that story: we are still in the middle of it and do not yet know its ending. Among many other available examples he would certainly choose the Fat-Eating Phobia that occupied the entire second half of the 20th Century.

Fear of Fat or Lipophobia

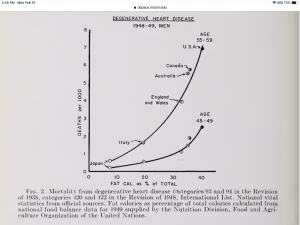

In the late 1940s, a fatal epidemic of coronary heart disease (hereafter, CHD) – was identified in the industrialised west. Deaths from this cause, especially in men, were more than double what they had been 30 years before. A simple and common-sense explanation was that people were dying of CHD, from their fifties onwards, at exactly the same rate as they had always done: there were simply now more people in that age cohort. In other words: good news, we are living longer. But scientists often scorn simple explanations in favour of explanations from the fields of esoteric knowledge which they have spent long years acquiring. Led by Ansel Keys (Professor of Physiology at Minnesota University) and Paul Dudley White (a leading cardiologist and head of the American Heart Association) the blame for the epidemic was laid squarely and solely at our affluent lifestyles, specifically: our over consumption of fat (in milk, eggs, butter, cheese and meat). In 1953, using UN Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) data, Keys published a graph showing a scary linear correlation between fat consumption and deaths from CHD in no less than six separate countries. This graph is reproduced below in its original unlovely form.

Ansel Keys’ graph, reproduced directly from his paper. It shows a near-perfect correlation between dietary fat intake and deaths from heart disease (CHD). Keys based it on FAO data collected in 1949 from middle-aged men in six countries. Reference: Keys A: 1953 Atherosclerosis – a problem in newer public health. J Mt Sinai Hospital 20, 118-139.

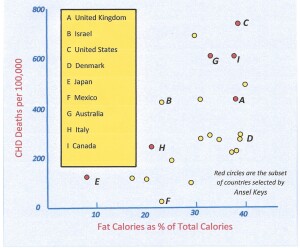

Three years later, a devastating critique of Ansel Keys’ 1953 paper was published by two medical statisticians (J. Yerushalmy & H. Hilleboe, NY State J Medicine, 1956 51(4): 2343-2354.). These authors graphed the data for all 22 countries available to Keys in the FAO data base. Looking at their graph (reproduced below): consider country A (United Kingdom), which has the same fat consumption as country C (United States), but almost half the rate of CHD; or country B (Israel), with half the fat consumption of the United Kingdom (A), but a near identical rate of CHD. By carefully picking an appropriate subset from the 22 plotted countries, almost any thesis could be proven. The authors concluded:

”Analysis of the available data shows that…the apparent association is greatly reduced when tested on all available countries for which data are available…it is the responsibility of the investigator to report on the basis on which the primary data were selected.”

Or in other, less diplomatic, terms: Keys had cherry picked his data to make the supposed correlation seem more impressive than it really was.

A graph of deaths from CHD against fat consumption showing all 22 countries in the FAO data base that was used by Ansel Keys. Re drafted from the original 1956 paper of Yerushalmy and Hilleboe. For discussion, see text.

Keys’ paper was a disgrace and should have been retracted. But it was not. Instead, it was widely circulated and quoted. It became heavily influential. In today’s terminology, the idea behind it went viral. Yerushalmy and Hilleboe were too late. Like a virus from a Wuhan Lab, the meme had already escaped from Keys’ flawed paper and begun its long march through the institutions, where group think, peer pressure and the emergence of post-normal science provided fertile ground for its rapid spread.

(Interesting aside: US Army rations during WW2 were devised by and named for Ansel Keys. They were called “K-Rations” and much hated by the troops).

A quick selection from my 21st century fridge to illustrate the demonised “ Frankenfoods” of the 20th.

A quick selection from my 21st century fridge to illustrate the demonised “ Frankenfoods” of the 20th.

Through the eighties and nineties, THE SCIENCE was declared settled. In 1987 and 1988, the American Heart Association (AHA), the American Medical Association (AMA), the National Academy of Sciences (NAS), the Office of the US Surgeon General (OSG), the US National Institute of Health (NIH), the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the American Dietetic Institute (ADI) had all climbed onto the bandwagon. Other similar Institutions throughout the western world followed suit. This alphabet soup of acronyms “urged Americans from the age of two upwards to go on restricted (low fat) diets in the hope of preventing CHD.” (My emphasis.)

The US Surgeon General in his report (July 1988, 700-pages) claimed that the evidence that fat consumption was responsible for two thirds of deaths in the United States was “even more impressive than that for tobacco.”

And the money flowed in as a result of the scare. The National Heart Institute annual budget of $1.5 million in 1948 soared to $132 million by 1962. And it continued to rise. The American Heart Association budget of $100,000 in 1945 reached $26 million by 1961. And it continued to rise. Big food processing companies paid the AHA handsomely for the right to claim their product was HEART FRIENDLY with a large, red, AHA-approved, tick on their packaging ( √ remember these?). Even boxed products from Mr Kellogg, so laden with sugar that they should have been sold in small measured quantities at the confectionery counter, carried this tick.

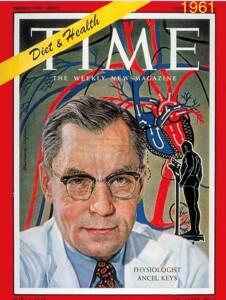

But there remained a few irritating grains of dirt in the shoes of the lipophobes. Many sceptical scientists, presumably from the 1.1% who had said “no” in the US Senate Survey, pointed out the weakness of the actual evidence for the diet-CHD connection. Perhaps the most influential of these was John Yudkin, Professor of Nutrition at the University of London. In the early seventies, Yudkin criticised the evidence relied on by the alarmists and, in particular, repeated the 1956 criticism of Ansel Keys seminal paper (where Keys had cherry picked data to prove a linear correlation between CHD and fat consumption). Keys ducked and weaved but never acknowledged the point. Instead, he directed critics to a much larger and long-term study that his Institute was then undertaking which (he was supremely confident) would eventually validate the diet-heart connection[2]. But Keys was by this time bullet proof. He was backed by the Institutes and the Academies, he was backed by the Politicians and the media, he had appeared on the cover of Time magazine.

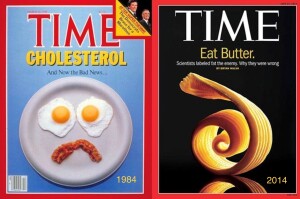

Time magazine, ever the bellwether of current fashionable opinion, promotes the scare in 1961: Ansel Keys at the height of his fame and influence

Time magazine, ever the bellwether of current fashionable opinion, promotes the scare in 1961: Ansel Keys at the height of his fame and influence

The scientific establishment pressured the University of London, who responded by cutting Yudkin’s research funding, forcing him to resign his professorship[3]. Thus, were lone sceptics dealt with in the 1970s. An early example of the Cancel Culture. It could have been worse: today Yudkin would also have been subject to ad-hominem attacks on Social Media …“in the pay of Big Dairy”… perhaps, and the pejorative slur label of “denier” would have been applied to him. They were more polite back then.

The other assault at this time on the dietary fat paradigm came from the Feminists. Women die from heart disease at a much lower rate than men. Scientific Institutes and Governments are run by men (this was 1978). The scare was therefore a man-thing and was diverting medical research funds away from areas of female concern, such as breast cancer. But here the American Cancer Society stepped into the breach and claimed (based on similar weak epidemiological evidence to that used by their heart colleagues) that breast cancer, too, was linked to dietary fat[4]. The feminists were thus safely co-opted to the scare. (A cynic might argue that the Cancer Society were merely protecting their share of the medical research dollar.)

But eventually, as more and more large sample, long-term studies became available, the tide of evidence forced a turnaround in mainstream opinion. Major data reviews (meta-analysis) conducted by Cochrane Collaboration[5] were carried out in 2000 and updated again with fresh evidence in 2001, 2004, 2007 and 2012. Their unequivocal conclusion, based on dozens of trials, involving tens of thousands of participants was: “There are no clear effects of dietary fat changes in total (cardio-vascular) events”[6]

A further independent meta-analysis by S. Berger and co-authors in 2015 examined even more trials, carried out over a 40-year period and involving 360,000 randomly-selected participants, concluded: “dietary cholesterol did not significantly change serum triglycerides or very low density (LDL or “bad” cholesterol) lipoproteins”[7] My bracketed insert.

The above quotes are from just two of the many early 21st century meta-analyses of the vast late 20th Century Fat Trials. So many meta-analyses that one could have conducted a meta-analysis of the meta-analyses. But there would have been no point. They all reached similar conclusions.

The scare was over. There were no apologies, no mea culpas from the scientific “experts” who had for decades pushed unsafe conclusions, with god-like certainty and ex-cathedra authority, in an area that they knew was complex and poorly-understood science. And in the process, enriched themselves, and their Institutions greatly.

Time Magazine recants in 2014

The scare was over, good science had driven out the bad. Or had it? As I write this in 2019, although the rhetoric is toned down and “can” has been substituted for “will”, outdated dietary advice is still out there. The American Heart Association now recommends: “dietary cholesterol should be limited to 300 mg per day” (i.e. not much more than that contained in one large egg). The UK National Health Service currently offers this advice: “eating lots of saturated fats can raise your cholesterol level and increase your risk of heart attacks.“ And this, from the Australian Heart Foundation: “the best fats to include in your diet are monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats. Eat more of these healthy fats to reduce the risk of heart disease.” The Dietitians Association of Australia: “limit intake of food containing saturated fats…“ The reasoning behind this false and out-of-date advice would seem to be: while the heroic clinical trials of the last century show no correlation between dietary fat and CHD, they do not actually prove that no such link exists (since it is almost impossible to prove a negative). A hangover from the old scare, a reluctance to admit error and the Precautionary Principle does the rest.

While the majority of scientists (or at any rate, those aged under 40 and operating outside the entrenched prejudices of the Institutions) interested in this subject are aware that the scare is over, the majority of the public do not. After a half-century of indoctrination, fear of dietary fat in is now imprinted in our collective psyche as a folk “knowledge”, and that might take a generation to disappear. The linkage in most peoples mind between the two English-language meanings of the word “fat” is hard to overcome. If you doubt this, just visit the shelves of your local supermarket where the labels such as “no fat”, “low fat” or “95% fat free” abound.

As Thomas Kuhn in “The structure of scientific revolutions” (1962) points out, old paradigms do not suddenly collapse. They just slowly fade away as their former champions, one by one, are pensioned off and die. Or, as Max Planck reportedly, and more cynically, put it, “Science advances one funeral at a time”.

The great Global Warming Hysteria of the 21st Century

The parallels between the Lipophobic and the Global Warming scares are remarkably close. Let me count the ways..

- In a new and esoteric area of scientific research, complex and little understood, scientists make overconfident and overstated claims of potential disaster for mankind: doubts, caveats and alternative explanations are suppressed. More research is needed to avert this disaster.

- In spite of more research being needed, the claim is made that the Science is settled and an overwhelming majority of scientists support this view[8].

- The scare resonates with the modern zeitgeist of the secular industrial west: guilt about consumerism and affluence, fear that this is sinful, cannot be sustained and must inevitably, (somehow, anyhow) be punished.

- The scare stories attract media attention. The scare starts slowly, but a tipping point is reached where, blindsided by group-think, peer pressure, cultural bias, desire for money on offer and, yes, a noble desire to save the world, the small and undemocratic coteries of scientists who run the Research Institutes, the Learned Societies, the academic Journals and the Universities climb onto the bandwagon, each no doubt independently arguing that, since everyone seemed to believe, it must be true.

- Taken in by this bootstrapped plausibility, floods of government money start to flow to the institutions and individual scientists promoting the scare. New career paths open up.

- Legislation is enacted to alter the habits of the nation to counteract the supposed catastrophic effects of the scare.

- A feeding frenzy begins when large private corporations move in to exploit the situation by making profits from government and public.

- Sceptical scientists holding non-alarmist positions are subjected to ad-hominem attacks, have their research funding cut and their academic papers rejected. They can expect no promotion and may even lose their jobs.

- Various tricks are used to promote the scare. Through dodgy statistics, cherry-picking or just creative drafting, graphs are presented which promote worst case scenarios and conceal evidence which does not fit the narrative[9]

- When promoting a supposed Noble Cause, the end is easily seen as justifying the means. Among promoters of the scare, Noble Cause Corruption proliferates and is even defended[10].

Afterword

I leave the final words to Charles Mackay:

We find that whole communities suddenly fix their minds upon one object, and go mad in its pursuit; that millions simultaneously become impressed with one delusion, and run after it, till their attention is caught by some new folly more captivating than the first.

*******

Sources:

Much of the information in this post comes from the book: Fear of Food: A History of why we worry about what we eat. by Harvey Levenstein, Emeritus Professor of History, McMaster University, Ontario. (U. of Chicago Press, 2012).

I have also been inspired by reading Nutrition in Crisis: Flawed Studies, Misleading Advice and the Real Science of Human Metabolism (2019, Chelsea Green Publishing, 304 p) by Richard Feinman, Professor of cell biology at the State University of New York.

I have taken material from the excellent recent peer-reviewed paper by Irma J Koetze – Climate and fat wars: a new role for law. – published in 2017 by the Journal of Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 13 (1) . The paper covers similar ground to this blog from a legal perspective.

For the earliest description of post-normal science see; Silvio Funtawicz and Jerome Ravetz: 1990: Uncertainty and quality in Science for Policy. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 0-7923-0799-2. I have borrowed the phrase “bootstrapped plausibility” from Ravetz’s writings.

Other sources used are identified in the text or footnotes.

Footnotes:

[1] Around 2010-11, as a result of the collapse of the 2009 UN Climate Conference in Copenhagen (COP15), the leaking of the Climategate emails, the 12-year flat-lining of global average temperatures and the bitter Northern Hemisphere winter of 2010, proponents of CAGW were in disarray. As a defensive measure, the name Global Warming was changed to Climate Change. By this means, any extreme natural climate event (be it heat or cold, flood or drought, storm or calm) could be claimed as confirmatory evidence. Those who control the language control the debate: their theory, they hoped, would become unfalsifiable. In this essay I use the original term – Global Warming. This is, and remains, the primary metric for any discussion of the subject.

[2] This was his “Seven Countries Study”, begun in 1959 and continued for the next 40 years. Keys interpreted the results as supporting his thesis, but, as numerous critics pointed out, he did not adequately allow for other associated risk factors such as smoking, obesity, sugar consumption, exercise, social status etc… (see, Keys A (ed): 1980. Seven Countries: A multivariate analysis of death and coronary heart disease. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-80237-3)

[3] But John Yudkin had the last laugh. In retirement, he wrote the best-selling book: Pure White and Deadly (London, Davis Pointer, 1972, reprinted 2012) which was one of the first to flag the danger to health of excessive sugar consumption. Today, when fear of fat has faded, a surfeit of sugar survives as a major accepted health risk.

[4] Within a few years, better research had shown little substance to this alleged link.

[5] Cochrane is a highly respected and influential UK based charity, staffed by volunteers committed to providing a gold standard assessment of clinical trials.

[6] Hooper L & co-authors: Reduced or modified fat for preventing cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Library 2012, Issue 5. Published by John Wiley.

[7] Berger S and co-authors 2015: Dietary cholesterol and cardiovascular disease – a systematic review and meta-analysis. American J Clinical Nutrition. www.ncbi.nim.nih.gov/pubmed/26109578

[8] The climate doomsters have some way to go before they match the 98.9% support once claimed by the lipophobes. They have only managed 97% so far. Perhaps they are not trying hard enough? The surveys, of course, were self-generated and self-serving push-polls, designed to achieve a desired answer. In any case, scientific truth is never determined by a show of hands.

[9] Yes, Michael Mann, Keith Briffa and Phil Jones, I mean you.

[10] The late Steve Schneider, former editor of the journal Climate Change and an IPCC Lead Author, stated “..we have to offer up scary scenarios, make simplified dramatic statements and make little mention of any doubts we may have. Each of us has to decide what the right balance is between being effective and being honest.” (Discover, October 1989, pp 45-48). In this statement, at least, Schneider chose to be honest.

In an essay published by the Royal Society in 2010, Schneider wrote (about the 4th IPCC Report): “Despite the large uncertainties in many parts of the policy assessments to date, uncertainty is no longer a responsible justification for delay.” In other words, the Precautionary Principle must always be applied, no matter how great the uncertainty or the cost of the proposed solution.

*****

This essay was first written in December 2019 and extensively modified with some new material in February 2021.