The Copper Wars, called by some the Battle of Butte, took place from 1898 to 1906 between the Anaconda Copper Company and companies owned by Fredrick Augustus Heinze. One of the minor but significant players these wars was young Anaconda geologist Reno Sales (1876-1969). In his eighties, Sales wrote a book about his experiences int the war called Underground Warfare at Butte (1964). Much of this post is based on that book. Background details to the conflict are taken from “The Battle for Butte” (1981) by Montana historian Michael P Malone.

Butte Montana

In the late summer of 1864, a group of prospectors discovered placer gold in the alluvial gravels of Missoula Gulch, a tributary of Silver Bow Creek in NW Montana. A rush ensued, but the gravels were thin and soon exhausted and the gold miners moved on. But swarms of quartz veins, up to 30m wide and stained with secondary oxides of iron, manganese and copper, had been noted at surface over an area of 15 km2 throughout Butte Hill which overlooked Silver Bow creek to the north. Within 10 years, shafts sunk on these veins had discovered rich silver and lead ore and a new rush began. Butte Hill gave its name to an emerging and rapidly-growing boom town based on silver and lead mining.

One of the early pioneers of the silver boom at Butte was Marcus Daly. Daly was born in 1841 near Ballyjamesduff in County Cavan, Ireland. As a 15 year old he joined the Irish diaspora escaping the potato famine, arriving penniless and alone in New York in 1856. Travelling west, he learnt his trade as prospector and underground miner on the California goldfields and the silver mines of Nevada and Utah. In 1880, moving to Montana, Daly paid for $40,000 for the most productive silver vein on the field – the Anaconda. Two years later (1882) a crosscut from the 300-foot level of the Anaconda opened a 10 m wide vein of high-grade chalcocite (copper sulphide: Cu2S). Grades averaged 12% Cu, but locally reached 55% (Malone, 1981). Soon a new rush based on copper mining began at Butte as more and more bonanza copper veins were discovered and developed through numerous shafts and dozens of individual claims. All this coincided with a booming demand for copper as America began to electrify at the end of the nineteenth century: there were vast fortunes to be made at Butte.

The Butte mineral field was, and possibly still is, one of the biggest metal concentrations on the planet. Up to 2013, it had produced 9.8 million tons of copper along with very substantial tonnages of Zinc, Manganese, Lead, Molybdenum, Silver and Gold. As at that date, a resource of 4.9 billion tons of 0.49% Cu and 0.033% Mo remained to be mined (Houston and Dilles, 2013). Mining of copper and molybdenum in the Continental open cut continues to this day.

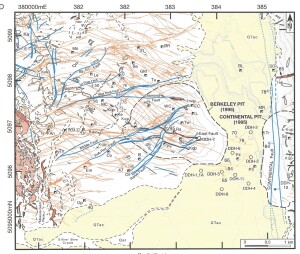

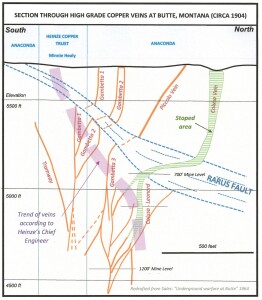

Figure 1: Geology of the Butte District. Orange lines are the mineral veins, blue lines are faults. L is the Leonard Shaft, Tw the Tramway Shaft, Ra the Rarus Shaft, Pe the Pennsylvania Shaft and A the Anaconda Shaft. Figure 3 from Houston & Dilles, Economic Geology, v108, 2013.

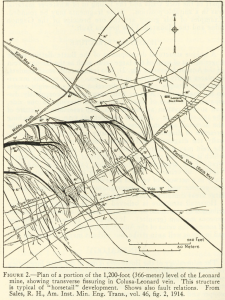

Figure 2: An example of detailed underground mapping at Butte by Anaconda geologists: the 1200′ underground level of the Pennsylvania mine. From Reno Sales 1914 Memoir: “Ore deposits at Butte, Montana.”

The Apex Law

The United States Law of the Apex (or Apex Law, or Apex Rule) was established and defined by the US General Mining Law of 1872 and applies to Federal public lands, located mostly in the Western States. It was based on the idea of winner take all. If you own the highest point – called the apex – of a mineralised vein, the Apex Law allows you to mine it down dip, even beyond the point where it passes at depth through the projected vertical boundary of your claim into an adjacent property. The apex holder can continue mining down the dip of the vein past his claim boundaries, but not along its strike (i.e. the horizontal extensions). Where the claim is rectangular with long sides parallel or sub-parallel to the vein strike (as would normally be the case) then the law states that mining at depth must be constrained within the projected vertical planes that define the two short sides of your claim: provided these sides are parallel and not divergent, and provided your claim was registered first. This is called your Extralateral Right. A Sub-Fault Apex is created where upward continuity of a vein ends against an intersecting fault plane. “Continuity” is the key word here. If the essential character and continuity of a vein can be demonstrated across a displacing fault, then the apex of the vein is the apex of the vein on the hangingwall of that fault and there is no sub-fault apex on the footwall.

What could possibly go wrong?

This absurd law, still in force today although seldom used, was written to legalize and codify what had become accepted mining practice in the Comstock silver district of Nevada – traditions probably brought there by immigrant Cornish miners and reflecting mining practice going back to pre-Roman times. But in the Comstock District (or in Cornwall for that matter) veins are usually discreet with relatively constant strike and dip. In Butte, by contrast, the mineralised veins form anastomosing swarms over an area of 15 km2, with variable strike and dip, and are cut and displaced by several shallow-dip normal faults (figure 1).

By 1887, virtually every surface vein had been located and pegged in the Butte area with hundreds of claims, dozens of head frames and numerous smelters. With bonanza grades and millions of dollars at stake, it is not surprising that the Apex Law provided the source for endless litigation, illegality and corruption. This led directly to the Copper Wars. But an incidental good that came from this sordid time in mining history was the genesis of detailed geological mine mapping.

The Anaconda Copper Company Consolidates the Field

By 1898, a round of acquisitions, financed by East Coast money men, led to extensive consolidation of ownership with the Amalgamated Copper Company becoming the dominant player on the field. Later, the Amalgamated Copper Company changed its name to the Anaconda Company. To avoid confusing the reader with a multiplicity of company names, I use Anaconda Company or just Anaconda for the remainder of the essay. You will find more detail on the corporate structure at Butte in footnote [1].

One of Anaconda’s first steps was to set up a well-resourced geology department to provide accurate surface and underground geological mapping of the vein systems and enclosing rocks. This was not just to provide information for mine development, but to arm themselves with exact scientific data to use in the litigation consequent on the Apex Law. The geology department was set up and headed by Horace V. Winchell. Among his first hires were rookie geologist Reno H Sales (in 1900, from Columbia School of Mines, New York City) and David M Brunton (an experienced Canadian geologist, inventor of the eponymous geology compass). Between them these three worked out the essential methods and procedures for accurate underground mapping of Butte’s geology. This involved the meticulous observation and measurement of all lithology, structure and mineralisation seen on underground rock faces, and the plotting and interpretation of the data on stacked Level Plans and Cross Sections throughout the mine. This scientific approach had never been attempted before at this scale or in such detail.

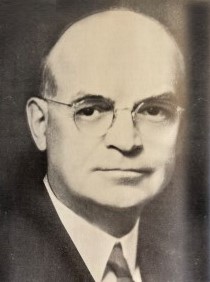

Reno H Sales in 1939

A New Player Comes to Town

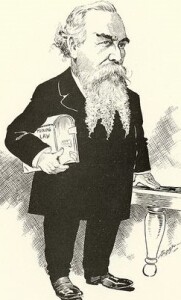

In 1898, at around the same time as the Anaconda company was being formed, a new and colourful character entered the scene at Butte. He was Frederick Augustus Heinze (or Fritz, to his friends).

Frederick Augustus Heinze in 1910

The son of immigrant German/Irish parents, Heinz was educated in both the US and Germany and graduated a mining engineer/geologist from Colombia School of Mines – the same school as Sales. After a brief stint working as a Mining Engineer with the Butte & Montana Company, he resigned and, with borrowed money and an inheritance of $50,000, created several companies to buy up a portfolio of many of the scattered small mines, smelters and claims in the district that had yet to be absorbed by Anaconda. This group were then amalgamated in 1901 into the United Copper Co. Where the Anaconda Company had set up a geology department to help defend their rights under the Apex Law, United Copper set up a legal department of 37 lawyers to achieve the same end. They were led by Heinze’s able lawyer brother Frank, and he set to work aggressively pursuing Anaconda through the courts for all real or imagined rights.

Heinze promoted himself and United Copper as the champions of the little miner against the creeping hegemony of the “evil” Anaconda and their Wall Street capital backing. He bought and edited a local daily newspaper – called the Reveille – which constantly attacked Anaconda and its senior employees, accusing them of corruption, perjury and other illegal activity. Butte locals referred to this paper as the Reviler, Sales called it a smear sheet. Heinze financed the electoral campaigns, at local, state and Federal Level, of politicians and judges whom he thought would be favourable to his cause (Malone, 1981). Heinze also used his considerable oratorical and demagogic skills to address crowds of miners from the Butte Hotel balcony, or from the Courthouse steps. He became a hero to his employees, reducing their working hours from 10 to eight hours per day whilst maintaining their daily rate of $3.75 – Anaconda were grudgingly forced to follow suit. District Judges William Clancy and Edward Harney, who were indebted to Heinze for their election (Malone, 1981) were particularly important to Heinze as they presided at the Silver Bow County Court where rulings on the application of Mining Law in much of the Butte District were given. Judge Clancy’s rulings in particular were so biased in favour of Heinze that it is hard not to believe there was a direct financial connection between them (although Sales is careful to make no claim of outright corruption).

District Court Judge William Clancy. According to Sales, his trident beard was usually decorated with samples from his morning’s breakfast. Image from Montana State Library.

District Court Judge William Clancy. According to Sales, his trident beard was usually decorated with samples from his morning’s breakfast. Image from Montana State Library.

Through the period 1898 to 1906 there were literally hundreds of individual battles between the two companies, and they were conducted not just in the courts and but as physical confrontations between miners at the rock faces underground. Many of these disputes ran simultaneously: some lasted, unresolved, for the full eight-year period of the conflict. Writing in his old age in 1964, Reno Sales was intimately involved in most of these battles and describes them in great detail in his book.

I retell the story of just two of these battles, to indicate the nature and scale of the conflict.

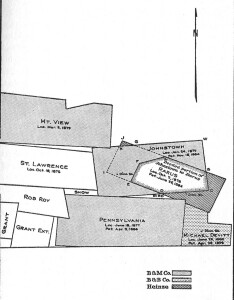

The Battle for the Pennsylvania

The most productive claim owned by United Copper was the Rarus. Ore coming up the Rarus haulage shaft provided the main feed for their concentrator and smelter located on the claim. The Rarus claim contained a system of interconnecting veins which dipped mostly south at a steep angle and so, with some wishful thinking, might pass at depth into the adjacent Pennsylvania and Michael Devitt claims of Anaconda (figure 4). The future of the small Rarus orebodies, and of its ever-hungry smelter, therefore critically depended on proving before a Judge that Rarus had extra-lateral mining rights under the Apex Law into the Anaconda ground.

Figure 4: A portion of the Butte mineral field showing claims held around 1901. The claims shaded with dots were owned by Anaconda. The Rarus claim (with no shading) and its extension to the SE (diagonal lines) were owned by Frederick Heinze and the United Copper Company. Other parties owned the unshaded claims to the west. Figure reproduced from Sales, 1964.

The situation was complicated by the large, northeast trending, shallow northwest-dipping, Rarus Normal Fault that ran through all these claims and displaced veins in the area by up to 120 m. The Rarus Fault was by then well-established through geological mapping – both at surface by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) and underground by the Anaconda Company. The Rarus veins lay on the hangingwall of the fault: the rich Pennsylvania and Michael Devitt veins that Heinze coveted were on the footwall. However, the direction of throw on this fault made it virtually impossible that the Rarus veins ever were continuous with vein systems of Michel Devitt and Pennsylvania. The The only way for Heinze to establish extra-lateral rights was to go to court and deny the existence of the Rarus Fault. To establish this, Heinze was able to obtain (“buy”, might be a better word) the testimony of a series of mining “experts” – one of them a former USGS geologist who, in that role, had put his name to the USGS geological map portfolio of the district!

Now, as it happened, the Michael Devitt claim lay outside the jurisdiction of Silver Bow County, so Heinze had to make his case before a Judge sitting in the Federal Court at Helena (the Capital of Montana). But, for his claim on Pennsylvania, he was able to make his case before his good friend, County Court Judge William Clancy. With a long line of expert witnesses for both sides, these court cases took weeks to resolve and were expensive for both parties. Unsurprisingly, Federal Judge Hiram Knowles rejected Heinze’s petition. Judge Clancy, on the same evidence, and by a stroke of the judicial pen, removed the Rarus Fault from the equation and granted Heinze extralateral rights to Pennsylvania. Heinze supporters claimed that Judge Knowles was a former employee of Anaconda, but there was no evidence to support that.

With appeals, supplementary legal claims and counterclaims and political maneuvering at both Local and State level, the Michael Devitt dispute went on for several years. Throughout that time United Copper were mining and hauling to surface through the Rarus shaft huge tonnages of ore illegally mined from both the Michael Devitt and Pennsylvania properties. Injunctions were issued, mine inspectors appointed. There were visits by US Federal Marshalls. Derisory fines for contempt of $20,000[2] were imposed on Frederick Heinze [3] and $2000 and $1000 respectively on his Chief Engineer Alfred Frank and the Rarus Mine Foreman Josiah Trerise. Heinze paid no heed to these legal impediments and continued to mine Anaconda ore.

So it came about that throughout the year 1903 both Anaconda and the United Copper were mining ore within the Pennsylvania Lease between the 400’ and 1000’ levels. The mining levels of the Rarus and Pennsylvania mines differed by 50’ in elevation. Both Anaconda (Pennsylvania) and United Copper (Rarus) sought advantage by advancing drifts[4] above the level of the opposition in order to extract the ore first. Almost daily, Pennsylvania workings would break into the workings of Rarus, and vice versa. When this happened, the openings were vigorously defended by opposing groups of miners, using high pressure water hoses, throwing rocks and smoke grenades or blowing lime. Strangely, according to Sales, the miners regarded all this as something of a game, and confrontation seldom continued after they returned to surface. But it would not stay a game for long…

Figure 5: Fighting in the Pennsylvania Mine in 1903. Reproduced from Sales, 1964.

But it would not stay a game for long…

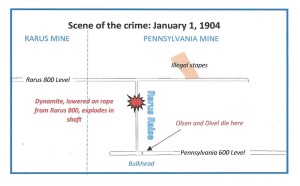

By October 1903, all attempts by Anaconda to gain access to Rarus workings so that they could document their illegal ore extraction for use in Court, had failed. With the approval of the Federal Court, Anaconda then commenced a raise[5] from the Pennsylvania 600 level to intersect the United Copper stopes on the Rarus 800 level (6). The raise would provide Anaconda with their own access to the illegal United workings (see figure 6). When Pennsylvania raise broke through into Rarus 800, Rarus miners tried to stop access by tipping mine waste into the new shaft and lighting large fires of rubber and leather where a downdraft would drive the fumes into the shaft and the Pennsylvania workings below.

Figure 6: The scene of the crime (not to scale).

Early on New Year’s day 1904, thinking the Pennsylvania mine would be deserted due to the holiday, Rarus miners lowered a large box of dynamite down the shaft and detonated it remotely. But although the Pennsylvania was quiet, two miners – Frederick Divel and Samuel Olsen – were working that morning on the 600 level. They had been given the special task of erecting an airtight wooden bulkhead near the foot of the shaft to block the noxious fumes of burning rubber. The blast from the explosion killed Fred Olsen instantly. Sam Divel was horribly wounded and died a few hours later.

It is hard to escape the conclusion that the dynamiting of the Rarus shaft was done with the full knowledge and probable instigation of Rarus management. However, at the subsequent Coronial Inquest, all employees of the Rarus Mine, from the foreman to lowest miner, swore on oath they knew nothing of the tragic event. Thomas Thyack, the Rarus Shift Boss who was on the level at the time of the explosion could not (or would not) give the names of the other miners present on the level because, he said, he only knew them by their first names. Attorney Peter Breen (United Copper) and Attorney L O Evans (Anaconda) were only prevented from coming to blows in the court by the intervention of the Coroner. The Jury’s verdict was manslaughter by person or persons unknown. Despite Anaconda’s offer of a $5000 reward for information, no one came forward, no one was ever charged with the crime.

Figure 7 Death of Fred Olsen

The Battle for the Leonard Deeps

Among the many scattered small claims bought by Heinze in his initial acquisition phase was the tiny 1.7 ha (4.2 ac) Minnie Healy.

To the south of Minnie Healy was the Tramway Claim in which Anaconda had majority ownership and United Copper minority ownership, but there was an existing court injunction against either company mining the Lease. The Tramway vein dipped north and was projected to enter Minnie Healy at depth. But Anaconda had the apex, and clear extra-lateral rights.

Immediately north of Minnie Healey were a group of claims wholly owned and actively mined by Anaconda. The ore was from the rich Coluso, Gambetta-3 and Leonard veins – which were amongst the most productive of the Butte field. These veins dipped steep south, converging below the 700’ level into a horsetail zone with outstanding tonnage potential (see Figures 2 and 7).

Figure 8: A vertical cross-section (view to west) of vein systems in the vicinity of the Minnie Healy claim of United Copper. Redrafted, with some additional annotation. From Sales, 1964

The Minnie Healy claim contained several small anastomosing veins with modest remaining copper reserves. These veins had variable but steep dips to the south, but there was no evidence that they might trend at depth beyond the vertical boundaries of the Claim. In spite of this, it is almost certain that the main reason why Heinze had bought Minnie Healey was to establish extralateral mining rights into the rich, adjacent Leonard-Colusa-Gambetta-3 vein system of Anaconda. Heinze could be confident of a favourable outcome since was a case that would be heard before Judge Clancy

And so began yet another of the endless series of apex hearings in the Silver Bow County District Court.

As an expert witness for Anaconda, Reno Sales showed the court a geological section (figure 8) based on detailed geological mapping using the methods that had been developed and carried out by the Anaconda geological team over the preceding few years. Appearing for United Copper, their Chief Engineer Al Frank produced a “geological” section which showed a broad, fuzzy mineralised zone dipping north from the Minnie Healey to enclose the coveted Leonard-Coluso-Gambetta-3 deeps below the 700 level in the Anaconda ground. Franks’ “geological” section was based on little more than wish fulfilment. It omitted the Rarus Fault [7] whose existence, of course, would have been detrimental to his position. Frank’s interpretation of the geology consisted of a section with a single broad dash line showing the course of the vein systems across the two claims. I have superimposed Frank’s “geology” as the broad purple dash line on Sale’s section (figure 8) .

The new geological science of accurate underground mapping won the day. Judge Clancy denied United Copper’s claim for extra-lateral rights and placed an injunction on their mining in the Anaconda ground. But in an absurd twist, he at the same time placed a similar injunction on Anaconda from extracting ore in their own mine from below the 700 level! Presumably, he thought this the Judgement of Solomon.

Although not quite the judgement he had sought, Heinze was undaunted. He reflected that what goes on underground is easy to conceal. An injunction to cease and desist only affects those companies who feel compelled to obey the ruling. With Anaconda excluded from the deep levels of their own mine, Heinze felt free to crosscut from Minnie Healey and commence illegal mining of the Coluso-Leonard deeps. As Anaconda subsequently found out when they eventually re-gained access to their mine, many thousands of tons of rich copper ore were removed. At the same time, in early 1904, Heinze constructed a secret crosscut to the south from the 1000’ Minnie Healy level and commenced to mine the Tramway vein, despite the previous Federal Court injunction against both Anaconda and United Copper from mining this vein.

Anaconda Wins the War

In February of 1906, Anaconda bought all the assets of Frederick Augustus Heinze with which they were currently in litigation (amounting to well over 100 active cases) for $10.5 million. United Copper retained some producing assets at Butte, but was now a minor player. Heinze took his money and left for New York with the intention of turning his great fortune (by then estimated at $25 million) into an even greater one. With his brothers Frank, Otto and Arthur, he set up a brokerage firm and acquired a bank. Through these they attempted to corner the stock in the United Copper Company so as to drive up the price and make a killing on the forced buying by short sellers (by that stage the Heinze brothers hoped to hold all the stock). But they miscalculated, the scheme failed spectacularly, and the brothers went bankrupt (8). The scandal caused a run on a number of banks and instigated the great Wall Street crash of 1907 and the subsequent creation, in 1913, of the Federal Reserve System (Malone, 1981; King 2012).

Heinze was down, but not yet quite out. He continued as the main shareholder and principal of United Copper, but its share price, which had fetched $80 in its glory days, fell to 80 cents and went into receivership in 1911. F. Augustus Heinze returned to the west and resumed his specialty of apex litigation in the Coeur D’Alene district of Idaho. He died in 1914 of cirrhosis of the liver. He was 44.

In 1906, Sales succeeded Horace Winchell as the Chief Geologist of the Anaconda Copper Company (see Reno Sales biography, Perry & Meyer, 1968). Under Sales, the Anaconda Company became renowned for the excellence of its geological work. The quality of mine mapping for which North American geologists are known was a direct result of the foundations laid by Reno Sales and his colleagues in Butte in the early years of the 19th century. The geology department of the Anaconda Copper Company was one of the important factors contributing to its growth through the 20th Century to become one of the world’s major mining houses.

Reno Sales was director of the geology department of Anaconda until his retirement in 1947. In his long career, he was awarded an honorary Doctor of Science degree from Montana State College (1935), the Penrose Medal of the Society of Economic Geologists (1939) and the Egleston Medal for distinguished engineering achievement (1942). He was President of the Society of Economic Geologists in 1937.

Reno Sales died in 1968 at the age of 82.

Some Final Thoughts

In 1906 the Anaconda Copper Company was left in almost complete possession of the field at Butte and so, in that sense, were entitled to be called the winner of the Copper Wars. Frederick A Heinze had surrendered the field: but he left richer by more than ten million dollars and would not have considered himself a loser. But winners get to write the history. That history is a satisfying one of Good Guys v. Bad Guys, where the guys in the white hats win through in the end after years of struggle and that is the story I have retold here. But was Frederick Heinze entirely the one-dimensional, opportunistic, greedy rogue portrayed by Sales? At the time, Heinze portrayed himself as a battler for the rights of miners, claim holders and small mining companies, threatened by a wealthy corporation with bottomless pockets. Even although Heinze’s main motivation was to build a wealthy corporation for himself, there is no reason to suppose that he was not sincere in his desire to improve the lot of miners. Undoubtedly, many in Butte during the nineteen noughties saw Heinze as their champion, and it is clear that his employees were fiercely loyal to him. I suspect that Anaconda’s motives during the war were not always pure and their own methods not always ethical or legal. Heinze’s efforts to counter the technical presentations of Anaconda geologists before the courts may appear ludicrous, but we are seeing this through the eyes of Reno Sales – hardly an unbiased reporter. Heinze did not have the luxury of a well-resourced geology department to support him.

********

The present author was an employee of the Anaconda company from 1976 to 1985.

Sources

King, Gilbert. September 2012: The copper king’s precipitous fall. Smithsonian Magazine. www.smithsonianmag.com

Houston R. A. and Dilles J.H.: 2013: Structural geologic evolution of the Butte district, Montana. Economic Geology, V108, pp 1397-1424.

Malone, Michael P 1981: The Battle for Butte – Mining and Politics on the Northern Frontier, 1864-1906. University of Washington Press, 281p

Meyer, C., Shea E. P., Goddard C. C., Staff: 1970. Ore deposits at Butte, Montana. In: Ore Deposits of the United States, Gratton-Sales Volume 2, AIME, pp 1373-1416.

Perry V. D. and Meyer C., 1970: Biography of Reno H Sales. In: Ore Deposits of the United States, Gratton-Sales Volume 1, AIME, pp xvii-xxiii.

Reno H Sales, 1914: Ore deposits at Butte, Montana. AIME Transactions v46, pp 4-106.

Reno H Sales, 1964. Underground warfare at Butte. Caxton Printers, 77 p.

Footnotes:

[1] Heinze began his Apex litigation in 1898 by taking out suits against Marcus Daly’s Anaconda Copper Company, the Boston and Montana Company and the Butte and Boston Company. All these were groups that had been enlarged from their original claim holdings by previous rounds of acquisitions. In 1899, mega-rich Wall Street financiers, including Henry Rogers and William Rockefeller of Standard Oil, bought out most of the major producers of the field including, inter alia, the Anaconda Co, the Parrott Co, and the Boston companies to form the giant Amalgamated Copper Company with Marcus Daly as its Chief Executive. In 1902 Heinze gathered his various companies together under the umbrella of the United Copper Company. Amalgamated Copper and United Copper were holding companies whose individual elements continued to operate and litigate at Butte under their own names. By 1910, when the whole Butte mineral field with all its mines, mills, smelters and railroads had finally come under the ownership of Amalgamated Copper, the name was changed to the Anaconda Copper Company. Anaconda continued to mine ore from the Butte district until 1983. In this text, for simplicity, I refer to the protagonists in the “wars” as the Anaconda Company and the United Copper Company.

Throughout the period of the “wars”, the corporate structures of both Amalgamated Copper and Heinze’s United Copper were actually more complex and byzantine than the simplified summary above would suggest. For example, in my account, I have omitted all reference to William A Clark who, along with Marcus Daly and F Augustus Heinze, was seen at the time as one of the three “Copper Kings” of Montana.

For anyone interested in the corporate and political history of the Butte Field I strongly recommend the meticulously researched book by Montana Historian Michael Malone.

[2] All dollar values quoted in this essay are those of 1900. For the equivalent in 2021 dollars, multiply by 30.

[3] A drop in the bucket, considering that by that stage he had already stolen, according to Sales, over $500,000 worth of high-grade copper ore.

[4] A drift is a horizontal opening driven along an ore body.

[5] A raise is an internal shaft driven upwards from an underground level.

(6) Mine levels are normally numbered by their depth below the shaft collar. Since the Rarus and Pennsylvania shafts only differed in elevation by 50′, it is difficult to understand why the Rarus 800′ level was above the Pennsylvania 600′ level. But these are the figures given by Sales. It makes no difference to the story.

[7] Franks did not have to prove this. The non-existence of the Rarus Fault had already been established to the satisfaction of Judge Clancy in an earlier hearing before him.

(8) Oil billionaire Nelson Bunker Hunt and his brothers tried the same trick with the silver market in 1979-80, with the same disastrous results (for them, at any rate).